ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Devon Balwit teaches/writes in Portland, OR. She has six chapbooks and three collections out in the world. Her individual poems can be found or are forthcoming in Glas as well as in The Cincinnati Review, apt, Posit, The Inflectionist Review, Bone Bouquet, Peacock Journal, and The Free State Review. Learn more at her website.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

We Call It That

June 15, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

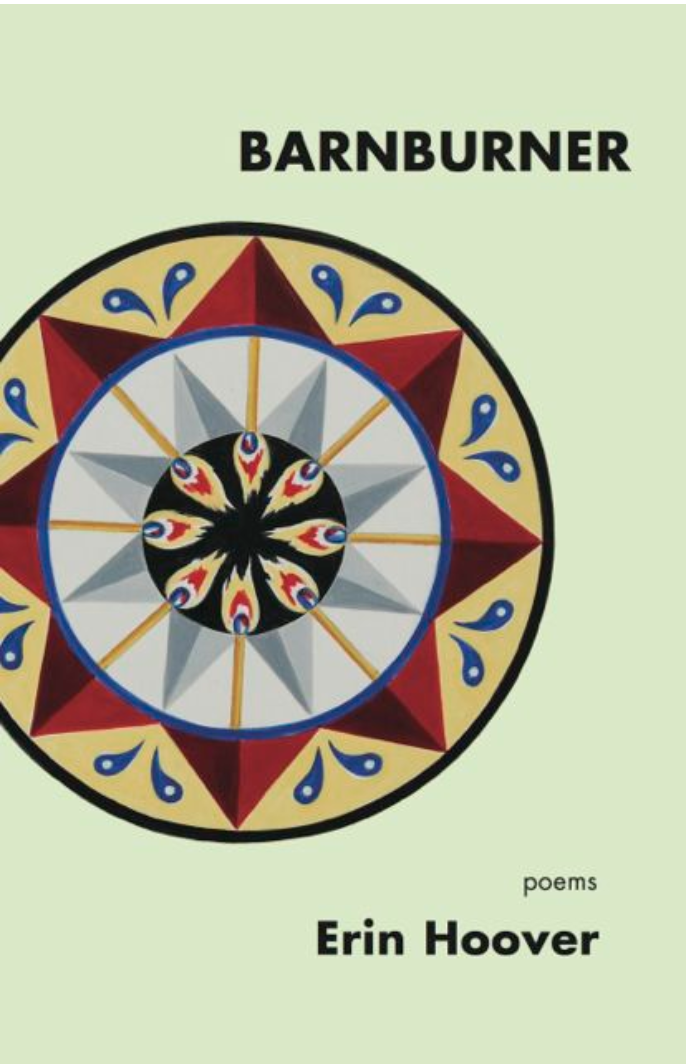

Believing in Understory: Review of Barnburner by Erin Hoover

Barnburner

by Erin Hoover

Elixir Press, 2018

“I believe there are always/words,” Erin Hoover claims in her poem “Reading Sappho’s Fragments” from her debut collection, Barnburner (Elixir Press, 2018). Throughout her collection, Hoover’s words work magic, suturing both the fractured body and fractured relationships. From the opening poem in which her speaker reports, “The call center made me an expert in my voice’s currency,” to the closing poem in which the narrator manages to talk an assailant out of a robbery, Hoover’s words make us pause and reconsider all we think true. And yet these words do not come easily in terms of ready tropes: “If Wittgenstein / could see us,” she writes, “he’d say there is no / ordinary language for what we are.”

Hoover’s voice is both scrappy and worldly. Like the best of witnesses, she partakes of a split vision—that of the scholarship kid and of the privileged glitterati, spending one night with her face pressed to asphalt after a blackout and another sipping rosé. In one poem, she might be manhandled and guilty of plenty of bad choices, while in the next, a woman who, when she’s had enough, is capable of imagining herself bashing her would-be rapist boyfriend across the nose with a fire extinguisher. She speaks in the voice of a young, naïve clubber and of the wiser older woman looking for a mentee for her hard-won wisdom: “If and when that friend arrives, let me / slip my present easily, sans ceremony, / over their bare shoulders.” She is both drugged up and clearsighted. Her young narrator primps for selfies, manipulating the male gaze, even as she herself later suffers from the manipulation of hateful on-line trolls. In the same poem, Hoover plays the role of decent citizen, stepping in to keep a post 9/11 gang of avengers from messing with an Arab store clerk, while then setting the record straight as to her true character: “More often than I’ll admit / I pass by an instance where I know / I should stop (…) and I go on past / and thought I sometimes circle back, by then, / of course, by then, / whoever it was is gone.” Above all, Hoover asks us to suspend easy judgments: “Don’t say you know yourself / unless you’ve stepped outside of it, / seen the shadow you cast / in your own bronze light.”

Even Hoover’s birthplace sets the scene for this doubling. Born within the evacuation shadow of Three Mile Island, she grew up amidst denial — everyone terrified of radiation while at the same time pretending all was as it appeared to be on the surface, suburban normalcy. “…everyone / has to live somewhere (…) / No choice but to count / our own bodies as safe to roam / inside, protected in our skin.” In another poem, Hoover writes, “In our subdivision, all the green / is curbed and contained,” while she and her junky friend M. are anything but, doped-up on the front porch.

Hoover is also unsparingly honest about how we fall short. In one poem, she confesses: “My nights then / were transcendent in their flaws.” In her poem “Barrier Island,” what seems like a successful connection between her and a couple of strangers goes south as they steal her money and scram when she trustingly leaves her purse behind to go to the restroom: “How nice they were, good / at being nice. How they seemed like friends.” And she, herself, is guilty of similar betrayals of genuine niceness. In one poem, she speculates about the estrangement and isolation her young nephew is feeling as he goes off to bed alone, yet she does nothing to broach that gap. “I want to sneak out / and whisper (…) / make an apology for how / jagged childhood is,” but she doesn’t. She, as most of us do, just hopes for the best or engages in wishful thinking: “I’ll never tell him / to be brave, but if I love him / he will be.” When, as a teen, she and her boyfriend find the remains of a fetus in a bag by the side of the road, she lets the boy talk her into leaving it there: “We drove away,” she confesses. “Of course / we did. What wouldn’t I have traded then / for the balm of male affection.”

Even as they explore a wide range of topics — our fraught relationship with the technologies we have created, our desperate search for love in all the wrong places, our self-medication, our work-lives, our hunger for that which outlives us (whether children or creative work) — the poems in Barnburner form a cohesive whole. Images and words recur. Take for example, that of pulling, In “The Tiniest of Shields,” this means a seemingly innocuous act that focuses all the terror of childhood: “We pulled the lever that lurched / alive our toy, set the horses trotting / in a circular shriek.” In “Temp” and “The Lovely Voice of Samantha West,” it means the pulling of work shifts, doing what one must to pay the bills even if it doesn’t feed the soul. In “What Kind of Deal Are We Going to Make,” the verb appears thus: “he asked me to lift / my skirt, and I did, pulled it to the bloom / of my upper thigh.” Finally, it means our own scalping: “With our history, / second nature now to draw the knife against our own crowns, and pull.” As a reader, it pleases to come across such resonant “through composition.”

In short, these are poems no reader should miss, poems that make us wince and sober us up. Hoover exposes her narrator’s youthful naiveté, and yet traces her maturation. If while reading them, we are not spared, paradoxically, we are in good hands. Hoover tells us: “I want / the ending we’ve earned (…) to stand / with you / in the path of the wallop.” If we are going down, we’ll go in good company.

Visit Erin Hoover's Website

Visit Elixir Press' Website

Barnburner

by Erin Hoover

Elixir Press, 2018

“I believe there are always/words,” Erin Hoover claims in her poem “Reading Sappho’s Fragments” from her debut collection, Barnburner (Elixir Press, 2018). Throughout her collection, Hoover’s words work magic, suturing both the fractured body and fractured relationships. From the opening poem in which her speaker reports, “The call center made me an expert in my voice’s currency,” to the closing poem in which the narrator manages to talk an assailant out of a robbery, Hoover’s words make us pause and reconsider all we think true. And yet these words do not come easily in terms of ready tropes: “If Wittgenstein / could see us,” she writes, “he’d say there is no / ordinary language for what we are.”

Hoover’s voice is both scrappy and worldly. Like the best of witnesses, she partakes of a split vision—that of the scholarship kid and of the privileged glitterati, spending one night with her face pressed to asphalt after a blackout and another sipping rosé. In one poem, she might be manhandled and guilty of plenty of bad choices, while in the next, a woman who, when she’s had enough, is capable of imagining herself bashing her would-be rapist boyfriend across the nose with a fire extinguisher. She speaks in the voice of a young, naïve clubber and of the wiser older woman looking for a mentee for her hard-won wisdom: “If and when that friend arrives, let me / slip my present easily, sans ceremony, / over their bare shoulders.” She is both drugged up and clearsighted. Her young narrator primps for selfies, manipulating the male gaze, even as she herself later suffers from the manipulation of hateful on-line trolls. In the same poem, Hoover plays the role of decent citizen, stepping in to keep a post 9/11 gang of avengers from messing with an Arab store clerk, while then setting the record straight as to her true character: “More often than I’ll admit / I pass by an instance where I know / I should stop (…) and I go on past / and thought I sometimes circle back, by then, / of course, by then, / whoever it was is gone.” Above all, Hoover asks us to suspend easy judgments: “Don’t say you know yourself / unless you’ve stepped outside of it, / seen the shadow you cast / in your own bronze light.”

Even Hoover’s birthplace sets the scene for this doubling. Born within the evacuation shadow of Three Mile Island, she grew up amidst denial — everyone terrified of radiation while at the same time pretending all was as it appeared to be on the surface, suburban normalcy. “…everyone / has to live somewhere (…) / No choice but to count / our own bodies as safe to roam / inside, protected in our skin.” In another poem, Hoover writes, “In our subdivision, all the green / is curbed and contained,” while she and her junky friend M. are anything but, doped-up on the front porch.

Hoover is also unsparingly honest about how we fall short. In one poem, she confesses: “My nights then / were transcendent in their flaws.” In her poem “Barrier Island,” what seems like a successful connection between her and a couple of strangers goes south as they steal her money and scram when she trustingly leaves her purse behind to go to the restroom: “How nice they were, good / at being nice. How they seemed like friends.” And she, herself, is guilty of similar betrayals of genuine niceness. In one poem, she speculates about the estrangement and isolation her young nephew is feeling as he goes off to bed alone, yet she does nothing to broach that gap. “I want to sneak out / and whisper (…) / make an apology for how / jagged childhood is,” but she doesn’t. She, as most of us do, just hopes for the best or engages in wishful thinking: “I’ll never tell him / to be brave, but if I love him / he will be.” When, as a teen, she and her boyfriend find the remains of a fetus in a bag by the side of the road, she lets the boy talk her into leaving it there: “We drove away,” she confesses. “Of course / we did. What wouldn’t I have traded then / for the balm of male affection.”

Even as they explore a wide range of topics — our fraught relationship with the technologies we have created, our desperate search for love in all the wrong places, our self-medication, our work-lives, our hunger for that which outlives us (whether children or creative work) — the poems in Barnburner form a cohesive whole. Images and words recur. Take for example, that of pulling, In “The Tiniest of Shields,” this means a seemingly innocuous act that focuses all the terror of childhood: “We pulled the lever that lurched / alive our toy, set the horses trotting / in a circular shriek.” In “Temp” and “The Lovely Voice of Samantha West,” it means the pulling of work shifts, doing what one must to pay the bills even if it doesn’t feed the soul. In “What Kind of Deal Are We Going to Make,” the verb appears thus: “he asked me to lift / my skirt, and I did, pulled it to the bloom / of my upper thigh.” Finally, it means our own scalping: “With our history, / second nature now to draw the knife against our own crowns, and pull.” As a reader, it pleases to come across such resonant “through composition.”

In short, these are poems no reader should miss, poems that make us wince and sober us up. Hoover exposes her narrator’s youthful naiveté, and yet traces her maturation. If while reading them, we are not spared, paradoxically, we are in good hands. Hoover tells us: “I want / the ending we’ve earned (…) to stand / with you / in the path of the wallop.” If we are going down, we’ll go in good company.

Visit Erin Hoover's Website

Visit Elixir Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.