ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Sage Curtis is a Bay Area writer fascinated by the way cities grit and how women move through the world. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Juked, Vinyl, Glass Poetry, The Normal School and more. She was a finalist for the Rita Dove Award in Poetry and the Gigantic Sequins Poetry Award, as well as an Honorable Mention for the Wrolstad Contemporary Poetry Series. Her chapbook, Trashcan Funeral, is available from dancing girl press.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

We Think Differently (At Night)

June 5, 2019

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

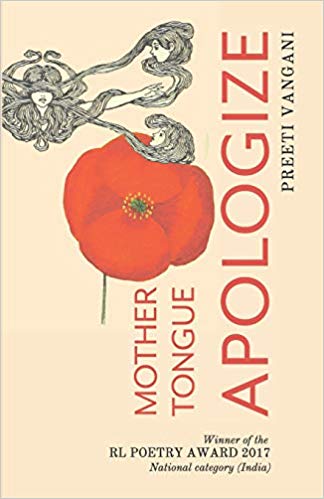

Review of Mother Tongue Apologize by Preeti Vangani

Mother Tongue Apologize

Preeti Vangani

RLFPA Editions, 2018

When starting Preeti Vangani’s debut collection Mother Tongue Apologize (RLFPA Editions, 2018), you’re transported immediately into a reluctant nostalgia. Halfway through the book, the speaker worries, quite literally, about giving too much of the past away too soon, but in that there the essential generosity of the text. Woven through the poems, the speaker experiences what is aptly described in the opening poem as “a Lonely Planet Guide titled 100 Getaways Without Mother.” It’s a journey the reader is welcomed into but feels deeply personal.

The collection is split into two sections: Mother Tongue and Apologize. Each section opens with the speaker’s body; its desires but also its gaps. By the fourth poem of the collection, “Stopgap,” the opening line reveals that the body we’re reading about will contain those gaps: “I opened another hole in my body/ so you could take more pleasure”.

The presence (or un-presence, in most cases) of the mother is what’s driving the speaker’s attention to the details of the past, even if it can be rather private at some points. The reader follows her through grief at all stages: the shock of knowing grief is coming, the present of seeing a loved one sick and waning, and the aftershock in all its forms. The intimacy the speaker is offering feels rare, somehow, like the reader must hold onto these moments with her.

What begins as “unremember”-ing however, becomes a way to keep the mother close, perfectly executed in the final images of “Ma San Ghazals as She Oiled My Hair”:

I want to lean on you like the resting on your shoulder/

your absence is a dark number equal to strands found in this hair.

“Chickoo,” you’d warn “don’t laugh at my off-key singing/

…you’ll remember it abound once I’m out of your hair.”

No matter how many times I’ve encountered that last line, my skin tingles with the anticipation of a mother who is both alive in the poem, but lost to the speaker, and the moments that hang between somehow. Vangani’s expert use of the ellipses as the lead in to the last line encompasses that wholly.

In all of this, is the story of a young Indian woman coming to her own, in her body and in the world — and in the places where those two things intersect. Most poems complicate that notion with the presence (or lack-there-of) of the mother.

The perfect example of this occurs toward the very end of the collection in “What Do You Have Left in Your Savings Account.” The prose poem begins, “A dead mother. A dead grandmother. Your body shaped like an outstretched hand,” and ends with the questions, “Why do you want to be a mother?”

Reading this collection is watching a debut poet play, with language, with form, with content, but is also an intense realization of how grief enters and exits the stages of our lives always as if it’s making its directorial debut. It begs the questions of motherhood, sexuality, girlhood, influence, and maturity. It asks us to interrogate how we hold our memories and our moments, and how much we’re willing to give away.

Visit RLFPA Editions's Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.