ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Claire Denson holds an MFA in Poetry from UNC Greensboro. She is a reader for The Adroit Journal and her work appears or is forthcoming in The Massachusetts Review, Hobart, and Sporklet, among others. You can find her at clairedenson.com.

January 19, 2021

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

On Becoming: The Poetry of Lindsay Bernal

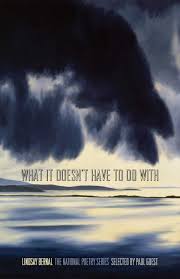

What It Doesn't Have to Do With

by Lindsay Bernal

University of Georgia Press, 2018

I met Lindsay Bernal in 2019 when she visited my MFA workshop and later that night when I introduced her before a reading. Like her poetry, she is thoughtful and careful; during her reading, she spoke quietly but with purpose. And when she thanked me after, I knew she meant it.

Her recent collection from which she read, What It Doesn't Have to Do With (University of Georgia Press, 2018), showcases through allusion — ranging from Ruskin to Pound to Modest Mouse — that it’s both embarrassing and painful to become. It is easy to see why the collection won the 2017 National Poetry Series and has since been published by University of Georgia Press in September 2018: the poems are at once complicated, beautiful, risky, and successful.

Bernal writes poems that portray the pervasive role of lust despite the nonlinear trajectory of grief. In What It Doesn't Have to Do With, the speaker recognizes her role as a young woman in the midst of growth. In conversation with her grief poem “No Echo,” the final poem “Postcard From Mazunte” employs sex as a coping mechanism. The speaker is able to escape her mind through her body, and to feel physically grounded:

What It Doesn't Have to Do With

by Lindsay Bernal

University of Georgia Press, 2018

I met Lindsay Bernal in 2019 when she visited my MFA workshop and later that night when I introduced her before a reading. Like her poetry, she is thoughtful and careful; during her reading, she spoke quietly but with purpose. And when she thanked me after, I knew she meant it.

Her recent collection from which she read, What It Doesn't Have to Do With (University of Georgia Press, 2018), showcases through allusion — ranging from Ruskin to Pound to Modest Mouse — that it’s both embarrassing and painful to become. It is easy to see why the collection won the 2017 National Poetry Series and has since been published by University of Georgia Press in September 2018: the poems are at once complicated, beautiful, risky, and successful.

Bernal writes poems that portray the pervasive role of lust despite the nonlinear trajectory of grief. In What It Doesn't Have to Do With, the speaker recognizes her role as a young woman in the midst of growth. In conversation with her grief poem “No Echo,” the final poem “Postcard From Mazunte” employs sex as a coping mechanism. The speaker is able to escape her mind through her body, and to feel physically grounded:There’s no disembodiment: I am my hips

Moving above him, my chest caving in;

[...]

This a-way. This a-way. This far away from grief.

Even when writing about pornography and performance art in “The Pre-Raphaelite Effect,” the speaker cannot help but focus on the interiority of the central female figure. She asks, “Is she faking? Is she faking?” and later: “when she closes her eyes, where does her mind go?” then answers: “...somewhere far.” Bernal’s poems contain a strong erotic energy consistent with the speaker’s youthful urgency. Still, each sexual reference within a poem is about something else, something more intimate and personal, an interior world not seen. Always containing a hint or more of despair.

In “The Pre-Raphaelite Effect,” the speaker adds self-awareness into the mix, providing a lens of shame:

My head between my knees,

I couldn’t take the onslaught

of spring, my part in it:

the trees’ showy leaves,

the flowers slowly opening.

Here we see the speaker’s resistance to growth. As we progress through the cohesive collection, this ambivalence unfolds and grows apparent. When describing the figure on a sculpture in “Rodin’s Fallen Caryatid,” Bernal writes that its facial expression perhaps conveys “woe, love, whatever.” This triad is tinged with youthful sarcasm yet possibility, suggesting hope despite its cynical tone.

Personal growth is full of ambivalence and uncomfortable self-awareness. It is not uncommon to find a speaker struggling with becoming, nor is it difficult to find one who alludes to Modernist and Greco-Roman-inspired work. But Lindsay Bernal’s passion for the Romantic and the Modern—intertwined—is distinct still more when paired with the speaker’s specific grief, desires, and Strandian case of Wherever I Go, There I Am. The speaker of her collection absorbs art and place then presents them back within her own context, transformed.

Bernal’s poetry thrills as much as it illuminates. Her collection, though it works through shame, is presented shamelessly — emotion displays itself across the page. In “Apologia,” she writes: “I’m sorry I subjected you to such bad art.” Clearly, the poet has come a long way from the speaker of that poem.

Visit Lindsay Bernal's Website

Visit University of Georgia Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.