ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Stephen Furlong received his M.A in English from Southeast Missouri State University. His poetry, book reviews, and interviews have appeared in Yes, Poetry, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, and Pine Hills Review, among others. He currently works at FIVE:2:ONE as a staff reviewer and can be found @StephenJFurlong on Twitter.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

Nostalgia

September 18, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

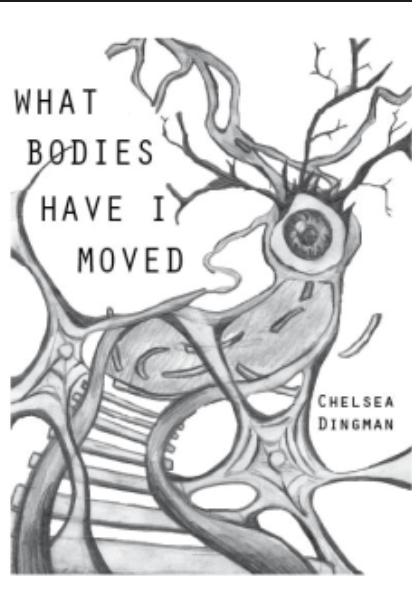

Review of What Bodies Have I Moved by Chelsea Dingman

What Bodies Have I Moved

by Chelsea Dingman

Madhouse Press, 2018

When I think of Chelsea Dingman’s poetry, I think of the opening line I read from Dante’s Inferno that has been lodged in my brain: “In the middle of our life, I found myself in a dark wood, for the straight way was lost.” The duality of the word found serves right because Chelsea Dingman’s poetry navigates difficult topics, but by bringing them to light and exploring the strife and struggle of herself and family, there is discovery. It is no accident that discovery and recovery are paired words as her chapbook, What Bodies Have I Moved (Madhouse Press, 2018) attempts to recover the story of a speaker from almost a hundred years ago: an emigrant from Poland to Canada during the mid 1920s. Speaking to this point, Dingman said in an Adroit Journal interview with forthcoming Glass Poet Kwame Opoku-Duku: “I think that obsession came out of feeling a little bit cut off from home, and how you can raise kids so far from where you began, and where your ancestors began, and how they can lose track of their lineage that way.” The success of Dingman’s book is in its duality as compass; it searches and finds a way towards home.

One of the great strengths of Chelsea Dingman’s poetry is the visceral nature wielded with such tenacity and dedication to get to the heart of narrative. Toni Morrison speaks to this point in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir (Houghton Mifflin, 1987) by calling the writer’s rush of imagination “flooding”, and Dingman’s poems serving as floods allow us readers to see the power and the erosion, the strength and the recovery. That strength is startling and is my favorite quality of Dingman’s poetry and something I aspire to when I sit down to write. An example of this visceral writing and flooding is in the poem “Mapping the Interior”:

My mother says she won’t go

anywhere that she can’t smell

the Black Sea, run her fingers over ridges

in a sky, white & seizing. She doesn’t know

roads that refuse tragedy. A different

tongue to speak with. Why would I trade

one ruin for another?

The calculated line breaks allow for that dagger of a first line as well as duality when speaking of the ridges in the ocean and sky both. That strength of nature imagery showcases the flooding mentioned earlier, while also speaking to the mysterious unknown, which leads to fear. While the italics serve as voice indication, I have also played this poem in my brain so much that I imagine the voice to be shaking and unstable, which by use of italics, heightens the emotion. Additionally, given the historical context of the speaker, it’s vital to mention that Poland (while not an independent state during World War I) saw brutality of battles which makes the uncertainty mentioned in the fourth and fifth line even more haunting. Pairing with the uncertainty of this poem, there is also exasperation and desperation with lines like “I can’t//offer her a deviation from this hunger” and “I will cut myself off from this sun.” These attributes are further heightened by the use of tercets because it is unsettling and arresting. It’s as though the poem is just getting steam and then there’s a break; it truly is a successful choice by Dingman. The poem’s close showcases the fear and instability present in the speaker’s life, Dingman writes:

… She, the unwanted tenant, door open

to rifle & bayonet, to all goats & god-

fearing men who mean her harm.

By use of an open door, we see the characters of this poem truly vulnerable to all potential issues and fears — this is even furthered by a timely line-break by Dingman. By breaking up god-fearing, Dingman is able to illustrate the jilting of a higher power felt, while also showcasing “men who mean her harm”. The dueling nature of the language is fascinating and calculated which showcases Dingman’s strengths.

What Bodies Have I Moved was a challenging, but ultimately rewarding, read which left me with great respect and admiration for Chelsea Dingman. Dingman very rightly received great acclaim for her debut Thaw (University of Georgia Press, 2017) but this chapbook from a budding press deserves attention for its use of voice and entanglement of familial ties and histories with landscapes and longing for home. To close, I think of Dingman’s lasting line from the poem “Ghosting”: Only after loss is everything new. When I think of that line, I think of the loss of home, language, and voice as it relates to the collective narrative Dingman creates. But, as a result, the everything new the chapbook creates is a renewed connection between Dingman and her family, but also a renewed connection for the reader in understanding the role of history as woven by visceral language and timely, nuanced line breaks. The collection is careful and calculated and truly reveals the dexterity of language that Chelsea Dingman is known for.

Visit Chelsea Dingman's Website

Visit Madhouse Press' Website

What Bodies Have I Moved

by Chelsea Dingman

Madhouse Press, 2018

When I think of Chelsea Dingman’s poetry, I think of the opening line I read from Dante’s Inferno that has been lodged in my brain: “In the middle of our life, I found myself in a dark wood, for the straight way was lost.” The duality of the word found serves right because Chelsea Dingman’s poetry navigates difficult topics, but by bringing them to light and exploring the strife and struggle of herself and family, there is discovery. It is no accident that discovery and recovery are paired words as her chapbook, What Bodies Have I Moved (Madhouse Press, 2018) attempts to recover the story of a speaker from almost a hundred years ago: an emigrant from Poland to Canada during the mid 1920s. Speaking to this point, Dingman said in an Adroit Journal interview with forthcoming Glass Poet Kwame Opoku-Duku: “I think that obsession came out of feeling a little bit cut off from home, and how you can raise kids so far from where you began, and where your ancestors began, and how they can lose track of their lineage that way.” The success of Dingman’s book is in its duality as compass; it searches and finds a way towards home.

One of the great strengths of Chelsea Dingman’s poetry is the visceral nature wielded with such tenacity and dedication to get to the heart of narrative. Toni Morrison speaks to this point in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir (Houghton Mifflin, 1987) by calling the writer’s rush of imagination “flooding”, and Dingman’s poems serving as floods allow us readers to see the power and the erosion, the strength and the recovery. That strength is startling and is my favorite quality of Dingman’s poetry and something I aspire to when I sit down to write. An example of this visceral writing and flooding is in the poem “Mapping the Interior”:

My mother says she won’t go

anywhere that she can’t smell

the Black Sea, run her fingers over ridges

in a sky, white & seizing. She doesn’t know

roads that refuse tragedy. A different

tongue to speak with. Why would I trade

one ruin for another?

The calculated line breaks allow for that dagger of a first line as well as duality when speaking of the ridges in the ocean and sky both. That strength of nature imagery showcases the flooding mentioned earlier, while also speaking to the mysterious unknown, which leads to fear. While the italics serve as voice indication, I have also played this poem in my brain so much that I imagine the voice to be shaking and unstable, which by use of italics, heightens the emotion. Additionally, given the historical context of the speaker, it’s vital to mention that Poland (while not an independent state during World War I) saw brutality of battles which makes the uncertainty mentioned in the fourth and fifth line even more haunting. Pairing with the uncertainty of this poem, there is also exasperation and desperation with lines like “I can’t//offer her a deviation from this hunger” and “I will cut myself off from this sun.” These attributes are further heightened by the use of tercets because it is unsettling and arresting. It’s as though the poem is just getting steam and then there’s a break; it truly is a successful choice by Dingman. The poem’s close showcases the fear and instability present in the speaker’s life, Dingman writes:

… She, the unwanted tenant, door open

to rifle & bayonet, to all goats & god-

fearing men who mean her harm.

By use of an open door, we see the characters of this poem truly vulnerable to all potential issues and fears — this is even furthered by a timely line-break by Dingman. By breaking up god-fearing, Dingman is able to illustrate the jilting of a higher power felt, while also showcasing “men who mean her harm”. The dueling nature of the language is fascinating and calculated which showcases Dingman’s strengths.

What Bodies Have I Moved was a challenging, but ultimately rewarding, read which left me with great respect and admiration for Chelsea Dingman. Dingman very rightly received great acclaim for her debut Thaw (University of Georgia Press, 2017) but this chapbook from a budding press deserves attention for its use of voice and entanglement of familial ties and histories with landscapes and longing for home. To close, I think of Dingman’s lasting line from the poem “Ghosting”: Only after loss is everything new. When I think of that line, I think of the loss of home, language, and voice as it relates to the collective narrative Dingman creates. But, as a result, the everything new the chapbook creates is a renewed connection between Dingman and her family, but also a renewed connection for the reader in understanding the role of history as woven by visceral language and timely, nuanced line breaks. The collection is careful and calculated and truly reveals the dexterity of language that Chelsea Dingman is known for.

Visit Chelsea Dingman's Website

Visit Madhouse Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.