ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Anne Graue is the author of Fig Tree in Winter (Dancing Girl Press, 2017) and has work in SWWIM Every Day, The Plath Poetry Project, Rivet Journal, Into the Void, and One Sentence Poems. She has published reviews in Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Whale Road Review, and The Rumpus.

January 17, 2019

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

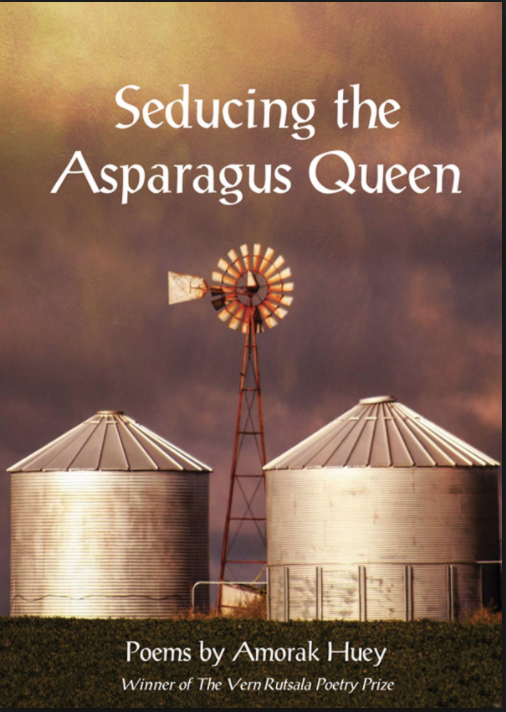

What Doesn’t Kill Us: A Review of Seducing the Asparagus Queen by Amorak Huey

Seducing the Asparagus Queen

by Amorak Huey

Cloudbank Books, 2018

Amorak Huey’s poems in his collection Seducing the Asparagus Queen (Cloudbank Books, 2018) have an awareness of purpose, an authoritative voice ready to give instructions, to say how things are, how they have always been, and why “Whatever doesn’t kill you fucks you up in some other way.” It’s a collection that reaches out to those of us born at the nebulous tail end of the baby boom who don’t quite know to which generation we belong or who our heroes are. What seems to matter is a constant question the voice in each poem, a little desperate, asks in its subtext: what does it mean to be human and participate in human activities that feel imagined even within the reality we’ve created for ourselves?

There is no shortfall of characters in Huey’s poems, and they come in many guises. Songs, games, television shows, clowns, and the letter X all are developed personalities that denote greater meaning and purpose. The clown appears early in the collection and reappears in different poems throughout. The first appearance is in “The Wikipedia Page ‘Clowns who Committed Suicide’ Has Been Deleted,” and provides a setting and speaks to what poetry should do. The 70s is represented by “babysitters in hot pants, // The Joy of Sex on the bedside table‧” and later “ten years of brown and green and orange shag, // plus all the wall-hangings, we are a generation / intimate with macramé.” The era is crystal clear in these images, and then the poet’s voice steps in to speak about genre and the purpose of poetry:

You think I’m telling stories

Now, that this would be better off as prose,

But let me tell you something real, and pay attention

Because I don’t do this often: every line breaks

Somewhere.

This awareness the poet shares in the middle of a poem is significant, especially in this early poem that seems to want to explain why the 70s was such a strange time to be growing up in the United States, and only poetry can show how the way in which Gen Xers turned out can only be described as inevitable. Following the poet’s interruption, the poem presents a list of foreseeable outcomes in stirring anaphora, letting Gen X off the hook with “It’s no wonder we grew up and gave // our children everything they asked for.” This poem does a great deal of expositional work for the reader, presenting the setting, the mood, and the tone that will remain consistent throughout Huey’s collection.

A prominent character in Huey’s focused collection is The Letter X who chooses his adventures, puts on a clown suit, and even imagines his own funeral. X is a variable that changes to suit the situation and alters the reality of each poem simply by its presence. In “The Letter X Chooses His Own Adventures,” the you addressed in each of the nine sections is instructed to “Make a world of your own choosing, / a place to eat, a place to rest — // all else is indulgence,” and in the last section reminded, “Everyone dies. What’s ridiculous / is it startles us every time.” In another poem, “The Letter X Drives from Tallahassee to Orlando to Break up With His Girlfriend Face-to-Face,” the speaker shares his uneasiness on the trip; he says, “I can’t see what’s coming — // something about the curve / of the planet, emptiness of the air, // not the heat but the humiliation / ahead of me.” His anxiety permeates the couplets ending in a crescendo of music played for reassurance. These and many more poems engage in such truth-telling in expressive lines and stanzas that are crafted in ways that convey a genuine perspective and an accurate realism.

A number of the poems in the collection begin with Self-Portrait, and these poems give the impression that the speaker is searching for definition and finding it in the popular culture that surrounded and nurtured Gen X. “Self-Portrait as a Game of Clue” is a poem about the isolating American family in which the picture of family life appears to be unwrinkled, but the speaker knows better amid “Everyone in the foyer with the awkward silence.” There’s been a metaphysical death that no one will discuss, yet everyone is suspect. Near the end of the collection, “Self-Portrait as Riker” refers to the character in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Relying on the reader’s knowledge of the show and the character, the poem explores the things that come up in a life and it turns out, the reader doesn’t have to know the show to understand the anxious feeling that things do not always turn out as planned and that may not be anyone’s fault. In life, “Plans change. Vision evolves. / The narrative ever at war with the self.” Just like a character in a TV show, we cannot always control the plot or accomplish everything in one lifetime. The self is reflected in the American culture that produced it, and the “Me” generation laid the groundwork for a generation searching for the self everywhere but here.

Nearly every line in this collection is memorable embracing humor and a wistfulness radiating from accessible language used in remarkable ways. The poems look back and appreciate the people and places that make up a culture of wondering what it’s all for and how we define being human in a contradictory world. In a poem that asks questions about the origins of the solar system while simultaneously discusses “pitching a comic book series about clown school” the speaker contemplates what he feels everyone should know, the poem’s title, “The Water in Your Glass Might be Older than the Sun.” As if telling a friend about his comic book plans, he shares this knowledge about water and how “it changes everything.” While we are whiling away our lives with trifling projects, we forget the origins of the universe and how we came to be here. This is the universal theme we should not forget. Huey’s poems won’t let us.

Visit Amorak Huey's Website

Visit Cloudbank Books' Website

Seducing the Asparagus Queen

by Amorak Huey

Cloudbank Books, 2018

Amorak Huey’s poems in his collection Seducing the Asparagus Queen (Cloudbank Books, 2018) have an awareness of purpose, an authoritative voice ready to give instructions, to say how things are, how they have always been, and why “Whatever doesn’t kill you fucks you up in some other way.” It’s a collection that reaches out to those of us born at the nebulous tail end of the baby boom who don’t quite know to which generation we belong or who our heroes are. What seems to matter is a constant question the voice in each poem, a little desperate, asks in its subtext: what does it mean to be human and participate in human activities that feel imagined even within the reality we’ve created for ourselves?

There is no shortfall of characters in Huey’s poems, and they come in many guises. Songs, games, television shows, clowns, and the letter X all are developed personalities that denote greater meaning and purpose. The clown appears early in the collection and reappears in different poems throughout. The first appearance is in “The Wikipedia Page ‘Clowns who Committed Suicide’ Has Been Deleted,” and provides a setting and speaks to what poetry should do. The 70s is represented by “babysitters in hot pants, // The Joy of Sex on the bedside table‧” and later “ten years of brown and green and orange shag, // plus all the wall-hangings, we are a generation / intimate with macramé.” The era is crystal clear in these images, and then the poet’s voice steps in to speak about genre and the purpose of poetry:

You think I’m telling stories

Now, that this would be better off as prose,

But let me tell you something real, and pay attention

Because I don’t do this often: every line breaks

Somewhere.

This awareness the poet shares in the middle of a poem is significant, especially in this early poem that seems to want to explain why the 70s was such a strange time to be growing up in the United States, and only poetry can show how the way in which Gen Xers turned out can only be described as inevitable. Following the poet’s interruption, the poem presents a list of foreseeable outcomes in stirring anaphora, letting Gen X off the hook with “It’s no wonder we grew up and gave // our children everything they asked for.” This poem does a great deal of expositional work for the reader, presenting the setting, the mood, and the tone that will remain consistent throughout Huey’s collection.

A prominent character in Huey’s focused collection is The Letter X who chooses his adventures, puts on a clown suit, and even imagines his own funeral. X is a variable that changes to suit the situation and alters the reality of each poem simply by its presence. In “The Letter X Chooses His Own Adventures,” the you addressed in each of the nine sections is instructed to “Make a world of your own choosing, / a place to eat, a place to rest — // all else is indulgence,” and in the last section reminded, “Everyone dies. What’s ridiculous / is it startles us every time.” In another poem, “The Letter X Drives from Tallahassee to Orlando to Break up With His Girlfriend Face-to-Face,” the speaker shares his uneasiness on the trip; he says, “I can’t see what’s coming — // something about the curve / of the planet, emptiness of the air, // not the heat but the humiliation / ahead of me.” His anxiety permeates the couplets ending in a crescendo of music played for reassurance. These and many more poems engage in such truth-telling in expressive lines and stanzas that are crafted in ways that convey a genuine perspective and an accurate realism.

A number of the poems in the collection begin with Self-Portrait, and these poems give the impression that the speaker is searching for definition and finding it in the popular culture that surrounded and nurtured Gen X. “Self-Portrait as a Game of Clue” is a poem about the isolating American family in which the picture of family life appears to be unwrinkled, but the speaker knows better amid “Everyone in the foyer with the awkward silence.” There’s been a metaphysical death that no one will discuss, yet everyone is suspect. Near the end of the collection, “Self-Portrait as Riker” refers to the character in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Relying on the reader’s knowledge of the show and the character, the poem explores the things that come up in a life and it turns out, the reader doesn’t have to know the show to understand the anxious feeling that things do not always turn out as planned and that may not be anyone’s fault. In life, “Plans change. Vision evolves. / The narrative ever at war with the self.” Just like a character in a TV show, we cannot always control the plot or accomplish everything in one lifetime. The self is reflected in the American culture that produced it, and the “Me” generation laid the groundwork for a generation searching for the self everywhere but here.

Nearly every line in this collection is memorable embracing humor and a wistfulness radiating from accessible language used in remarkable ways. The poems look back and appreciate the people and places that make up a culture of wondering what it’s all for and how we define being human in a contradictory world. In a poem that asks questions about the origins of the solar system while simultaneously discusses “pitching a comic book series about clown school” the speaker contemplates what he feels everyone should know, the poem’s title, “The Water in Your Glass Might be Older than the Sun.” As if telling a friend about his comic book plans, he shares this knowledge about water and how “it changes everything.” While we are whiling away our lives with trifling projects, we forget the origins of the universe and how we came to be here. This is the universal theme we should not forget. Huey’s poems won’t let us.

Visit Amorak Huey's Website

Visit Cloudbank Books' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.