ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Noor Hindi (She/Her) is a Palestinian-American poet who is currently pursuing her MFA in poetry through the NEOMFA program. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Winter Tangerine, Tinderbox Poetry, Glass Poetry, Jet Fuel Review, Diode Poetry Journal, Foundry Journal, & Flock Literary Journal. Her essays have appeared in or are forthcoming in Literary Hub and American Poetry Review. Hindi is the assistant poetry editor at The University of Akron Press and a reporter for The Devil Strip Magazine. Follow her on Twitter, or visit her website.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

Filthy Woman Writes a Letter

January 31, 2019

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

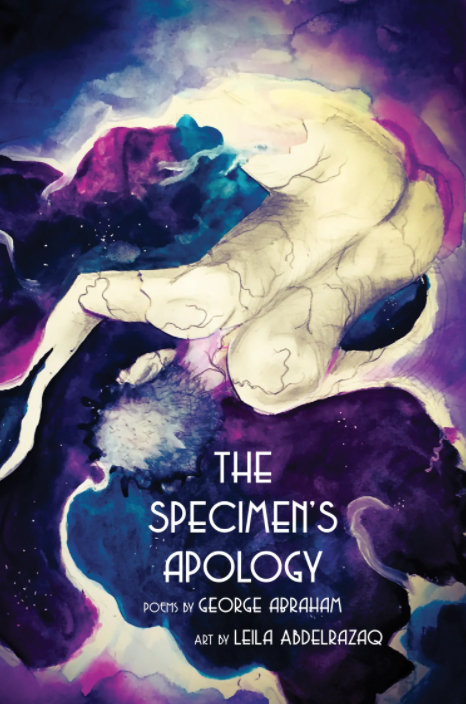

Review of the specimen’s apology by George Abraham

the specimen’s apology

George Abraham

Sibling Rivalry Press, 2019

George Abraham’s newest chapbook, the specimen’s apology (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2019), is both a protest against erasure, against colonization of the body and the homeland, and a yearning to exist outside of the binaries that restrict our freedom. Published with Sibling Rivalry Press, Abraham’s chapbook asks what it means to exist within the queer, Palestinian body, to reconcile family history and politics, all while celebrating the “tiny miracles” of our survival: “i woke up this morning. i woke up this morning” writes Abraham, despite the “search for home,” despite “the moment I wanted to die,” despite the body being “a mistranslation of itself,” Abraham “will write poems of olive tree & checkpoint.” These are poems of emotional fierceness, and as usual, Abraham holds nothing back.

From the very first poem, “ars poetica with waning memory,” Abraham plunges readers into the world of his speaker, taking risks with both form and content. This poem wrestles with the trauma of sexual assault, with remembering/misremembering, seeing/unseeing: “I came / on my own accord. i was never there. my stain, a small country…” The gaze of the other is interrogated in this chapbook, where the “you” becomes a “specimen” to be studied, constrained and defined, something we might call “human” or “spectacle.” In “binary.” the speaker begins, “once i had a body & that body was a [male/female] body. some days i contoured & dressed the [male/female] body…” In this poem, Abraham examines the tension between terrorist/freedom-fighter, conflict/occupation, rapist/lover, asking readers to grapple with these dualities.

The 48-page chapbook has a diverse selection of forms and styles. Fans of al youm: for yesterday & her inherited traumas (the Atlas Review, 2017) will be happy to see Abraham’s skillful use of erasure return, but in different ways. In “ars poetica in which every pronoun is a Free Palestine” Abraham writes, “FREE PALESTINE will die in protest & become / kite on fire…” I love this poem for its insistence on freedom, and its insistence that “FREE PALESTINE will exist / in no language.” In “the Palestinian/queer specimen’s Lexicon with Auto-Translate” Abraham uses a similar technique: “i don’t watch the news any more / [translation — i am worried my people might be on it]…” The tension between translation/mistranslation and what is said/unsaid is remarkable here. The poems in Abraham’s chapbook take up a lot of space on each page and draw readers in, visually. A few of them can be read multiple ways and disturb our usual reading experience.

I especially enjoyed Abraham’s use of Marwa Helal’s form, The Arabic, throughout the chapbook. These poems are meant to be read from right to left, and actively place English readers in discomfort by asking them to resist the way their eyes dart to the left side of the page, thereby dismantling what they see as superior. Abraham uses this form as a thread throughout the chapbook in this poems “maqam of moonlight, for the wandering,” and “maqam of moonlight, for the children of exile,” which is a title Abraham uses twice. My favorite is the last “maqam of moonlight” which reads, “— keffiyeh a wear to ways of hundreds are there / chest your let — flag like neck your across it drape…”

The poems in the specimen’s apology pull inspiration from medical textbooks, the video game Bioshock: Infinite, the US Department of Defense drone manuals, are in conversation with Tarfia Faizullah, Marwa Helal, and sit alongside artwork by Palestinian author and artist Leila Abdelrazaq. It’s difficult to imagine how Abraham is able to pull from so many different sources, but I admire this about his work. For example, something that really surprised me is Abraham’s use of the videogame, Bioshock: Infinite to talk about the cycle of abuse and trauma. Pulling from such an unusual source isn’t something I typically see in work by contemporary Arab-Americans, but it’s a fascinating use of a culture.

Throughout the chapbook, Abdelrazaq’s drawings both complement and work in tension with Abraham’s words. For example, the drawing on page 29 seems to be the core of the chapbook. The drawing is in black and white (like most of the others) and features two faces blended into each other, creating an interesting parallel. The chapbook is visually beautiful, and the multiple forms Abraham experiments with makes for an engaging reading experience.

the specimen’s apology places the queer, Palestinian body at center, and furthers the conversations that Arab-American and Palestinian writing communities have been having. This is a chapbook everyone should get their hands on.

Visit George Abraham's Website

Visit Sibling Rivalry Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.