ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Stephanie Kaylor is a writer from upstate New York. She holds a MA in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from the University at Albany and is currently finishing a MA in Philosophy at the European Graduate School. Stephanie is Reviews Editor for Glass: A Journal of Poetry and her poetry has appeared in a number of journals including BlazeVOX, The Willow Review, and altpoetics.

March 14, 2017

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

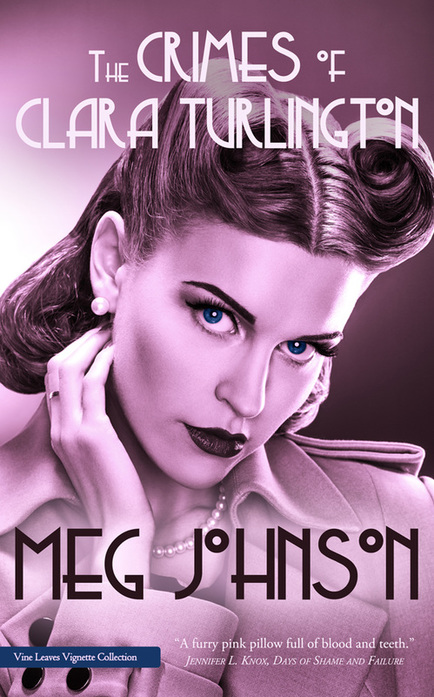

Review of The Crimes of Clara Turlington by Meg Johnson

The Crimes of Clara Turlington

by Meg Johnson

Vine Leaves Press, 2015

To read The Crimes of Clara Turlington is to huddle under the covers with your girlfriends and a flashlight at summer camp, staying up for story-sharing of both laughter and fright even after you're told "lights out." Though this collection of vignettes exploring different female narrators' lives, musings, and confessions was published in 2015, each poem in Meg Johnson's second full length poetry collection serves as a warning to the men of Trump's America.

The characters may not self-identify as feminist, and certainly may not be identified by others as being feminist, as they make their confessions — dreams of killing one's husband, for example, as we read of in "Nubs Gives Me Footie Pajamas." Nevertheless, these girls are undeniably dangerous to any patriarchal order. They ask questions.

In the poem "L," the narrator succinctly explores the danger of believing hegemonic narratives of femininity:

Strangers will think

I'm a drunk college

girl. But I'm a grown

Woman.

Each of these poems is sharp, short; a single musing each narrator divulges almost carelessly, as if thinking to herself while painting her toes. The impression they leave, however, is a haunting that only becomes stronger amidst this juxtaposition: the profound statements of the weight of being not only woman, but being subject, are carefully written by Johnson in varying tones free of any self-seriousness, sighed out in bubblegum breath.

This is not to say that these poems are all chipper; in "In Pseudonym, Illinois," for example, it is observed that

It doesn't matter

what I wear or don't

wear. It doesn't matter

that I have a face.

Rather, it is the succinct nature of these musings and the absence of any value claim that makes them unique to this collection. Similarly, in the poem "American Woman: Or, if the Three Original American Girl Heroines were Grown-Ass Women in 2013," 80's and 90's girls get the sequels to the stories we grew up on set in our contemporary world. Kristen, here an office worker with three sons and a husband, isn't "suicidal, but / she didn't mind thinking about death;" Samantha is twice divorced and drinking martinis, reminded that "The clock is ticking;" and Molly "reconciled with her father / after years of estrangement," but "She also knew he would continue to vote / Conservative."

To find an incongruity between these somber fates and the frivolities of the other women who unabashedly hold their own, however, is to miss the point that brings these narratives together: a woman can do everything "right" and still the world won't treat her with that reciprocity; it is because of this that a woman can explore these contradictions and subvert their patriarchal holdings in doing so, and to read the work of Johnson does just that.

Visit Meg Johnson's Website

Visit Vine Leaves Press' Website

The Crimes of Clara Turlington

by Meg Johnson

Vine Leaves Press, 2015

To read The Crimes of Clara Turlington is to huddle under the covers with your girlfriends and a flashlight at summer camp, staying up for story-sharing of both laughter and fright even after you're told "lights out." Though this collection of vignettes exploring different female narrators' lives, musings, and confessions was published in 2015, each poem in Meg Johnson's second full length poetry collection serves as a warning to the men of Trump's America.

The characters may not self-identify as feminist, and certainly may not be identified by others as being feminist, as they make their confessions — dreams of killing one's husband, for example, as we read of in "Nubs Gives Me Footie Pajamas." Nevertheless, these girls are undeniably dangerous to any patriarchal order. They ask questions.

In the poem "L," the narrator succinctly explores the danger of believing hegemonic narratives of femininity:

Strangers will think

I'm a drunk college

girl. But I'm a grown

Woman.

Each of these poems is sharp, short; a single musing each narrator divulges almost carelessly, as if thinking to herself while painting her toes. The impression they leave, however, is a haunting that only becomes stronger amidst this juxtaposition: the profound statements of the weight of being not only woman, but being subject, are carefully written by Johnson in varying tones free of any self-seriousness, sighed out in bubblegum breath.

This is not to say that these poems are all chipper; in "In Pseudonym, Illinois," for example, it is observed that

It doesn't matter

what I wear or don't

wear. It doesn't matter

that I have a face.

Rather, it is the succinct nature of these musings and the absence of any value claim that makes them unique to this collection. Similarly, in the poem "American Woman: Or, if the Three Original American Girl Heroines were Grown-Ass Women in 2013," 80's and 90's girls get the sequels to the stories we grew up on set in our contemporary world. Kristen, here an office worker with three sons and a husband, isn't "suicidal, but / she didn't mind thinking about death;" Samantha is twice divorced and drinking martinis, reminded that "The clock is ticking;" and Molly "reconciled with her father / after years of estrangement," but "She also knew he would continue to vote / Conservative."

To find an incongruity between these somber fates and the frivolities of the other women who unabashedly hold their own, however, is to miss the point that brings these narratives together: a woman can do everything "right" and still the world won't treat her with that reciprocity; it is because of this that a woman can explore these contradictions and subvert their patriarchal holdings in doing so, and to read the work of Johnson does just that.

Visit Meg Johnson's Website

Visit Vine Leaves Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.