ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Rachel Mindell is the author of two chapbooks: Like a Teardrop and a Bullet (Dancing Girl Press) and rib and instep: honey (above/ground). Individual poems have appeared (or will) in Black Warrior Review, Denver Quarterly, DIAGRAM, Foglifter, BOAAT, Forklift, Ohio, The Journal, and elsewhere. She works for Submittable and the University of Arizona Poetry Center.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

Insemination

April 30, 2019

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Am I / your calf / I am your calf: Cutting Synthesis in Kill Class by Nomi Stone

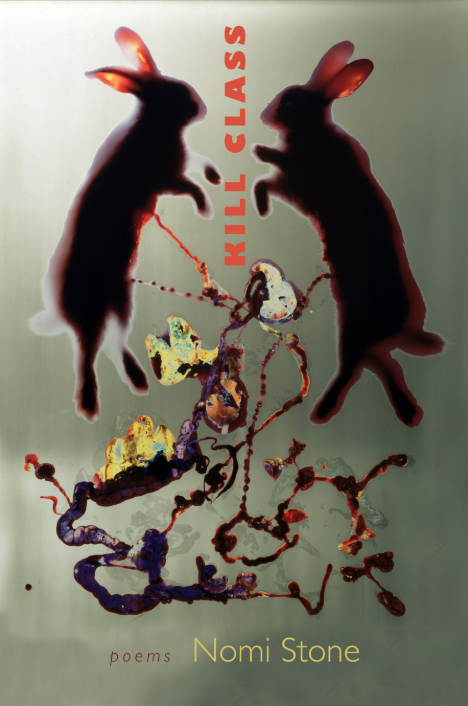

Kill Class

Nomi Stone

Tupelo Press, 2019

Nomi Stone’s latest collection, Kill Class (Tupelo Press, 2019), is extraordinary; extraordinary in its subject and in its execution. Inspired by Stone’s two years completing anthropological field work in US pre-deployment military training “villages,” the poems in Kill Class are brutal, beautiful, critical, and wise: the speaker intertwines her own experience, as an observer and participant in war games in the woods, with that of domestic soldiers and foreign nationals, the latter enacting the roles of interpreter, civilian, and traitor overseas. This book is necessary and unforgettable, not only for the culture it depicts but also for the exquisite and cutting craft of Stone’s prosody.

Kills Class is full of food, animals, and slaughter. The opening poem, “Human Technology,” includes a pig roasted on a porch, shared wine, and lebna: “Sir, my child was not with the enemy. / He was with me in this kitchen, making lebna at home / The yogurt still fresh on his wrist” (x). Wild onion and simulated chickpea soup appear throughout the text.

There is real food — the actors eat at Arby’s, drink tea, fry spam and eggs, and the soldiers consume in excess: “After shooting, we go to the buffet, and there is so much meat: / chicken and fat and cuts of hog, then banana pudding with / crumbled cookies. We eat so much it is awful, almost” (74). There is also real hunger, hunger that builds as the games run for extended periods. The speaker: “I have not eaten in a long time, and one / soldier hands me a clementine, the juice dribbles over my notes” (63).

There is also symbolic hunger and synthetic food. There is hunger among the “players” for better work and sustenance, for home. There are plastic grapes in the model internet café, and of the woods, we are told, “Green in here, gleaming / like being inside a fable / with stalls of fruit you can’t eat. / To go home, leave crumbs” (65). The desire for the real is very real.

Consumption is a vital theme here. In “The Anthropologist,” the speaker renames the surrounding roads of “Pineland,” the country where the action is set, for meat (“Pork Chop Hill, Ham Road, Chicken Lane”), and she is asked,

do I agree that through my

stomach, they will get

my heart? (6).

Nations are designated for feasting. Those on the wrong side must be made to “slice open the skin of their country” (x). Further on, “the country / is fat. We eat / from its side” (8), and to Laith, an interpreter, “you are of this country, / carved from its side” (9). In war, as a result of their words, individuals may be forced to consume one another. “absolutely the mouth / of knowledge if your neighbor / learns about what you’re doing / with the Americans — careful now, / this is war — he might eat you you / are the last fruit left on this street” (53).

The speaker is made to witness and participate in horrifying scenes. On the 4th of July, the soldiers attempt a tandem jump with a pig as a joke but it goes wrong and we assume the animal dies (55). The heart-wrenching, gut-churning title poem, “Kill Class,” centers on the speaker, nicknamed Gypsy by the soldiers, role-playing with them. They bring her killed chickens to prepare: “This is meat now. I turn them / into something” (48), but this is not enough. They want her to slaughter a rabbit, she is told she has no choice — begging the question who, in war, has choice and when?

The men make a circle

The pines make a circle

You need to hold

the legs. They are tying together

the legs the animal

screaming

Repetition is also central to the text — the necessity of repetition for practice and mastery, the unceasing, indistinguishable practices of real war. Stone repeats titles; we see the games “reboot.” Because the settings for these scenarios are assembled from boxes, and wounds come from kits, there is no need to ever stop. These are “collapsible houses / made for daily wreckage” (4), in this way not unlike bombed houses in real war. Stone makes regular use of the colon and the slash — the former implying (often false) equivalency or relationship, the latter emphasizing the fragmentation between simulated and actual.

In the face of repetition, discrimination is required. What is real? Who is guilty? “He tells me: in the occupied land we are the arm, they / are the weapon. The weapon / in this case is a person. Choose a person / who knows who is bad” (x). The task comes down to choice, when, read another way: who knows who is bad; who knows who is bad? And why should anyone be making this sort of determination? Stone writes: “Omar tells me the soldiers don’t know it yet, but all / the Iraqis in this village are in cahoots with the militia. The game says / figure out which bodies have turned the bright chill of gold” (3).

If a soldier cannot differentiate, they lose, they will lose. “Some / of the people over there are good / others evil… The game says figure / out which / are which” (16). In “Matrix: Which is Which,” Stone offers characters notes for herself (Gypsy) and each of the foreign actors. Of Omar, she writes, “Omar are you dead? Are you bad? Find out which is which” (9).

These the same sorts of choices played out in the soldiers’ and role-players’ lives outside of work, in search of extra work — the Walmart application has 70 questions and some involve customer scenarios (59). And the question of “which is which” hovers over the book at large, beyond who deserves to die in a game: can we still tell the difference between what is genuine and what is designed, conceived? And what, if any, is the difference between liberation and occupation (see p. 25)?

Stone writes:

I am in a war. No,

I am in a game

of war. No, I am in a painting (54).

These question are especially significant considering the distance implied by the speaker’s role as an anthropological observer. Stone asks of herself: “Anthropologist, why are you in this story” (80)? How is anthropology its own war game? It is understandable (if disturbing) that desensitization is essential for the soldiers to cope — “Willy / holds out his iPhone. “Honey, / check it out I played / killed” ” (17) — and humor is a strategy (“Commander: Do you take hot sauce on those ashes?” (43)). And yet, how is the speaker to embrace or forgo detachment? Stone is acutely aware of the complications her position creates.

The speaker is able to bridge some of the aesthetic distance of the war games’ stage directions and built sets with her command of Arabic, her genuine expression of interest, her willingness to participate (up to a point which is tested, along with concerns for safety, tested). Her possession of choice does set her apart — the choice to leave — as does her access — to academic context and etymology that both complicate and enhance her interpretation of events. Further, her practice is not always dissimilar from those she is observing, who must rely on manners and information to survive:

“Their Commander reminds them / to use rapport to get to the main point. Drink tea with them for an hour / at the very end, maybe you will get what you need. / I am learning how to be an anthropologist. Anthropologists are furious and want / culture back. Every day in this wood, I drink tea, fragrant and black / and wait very slowly / for them to open, and for me to open” (63).

Another role the speaker brings with her to Pineland is that of a lover surviving loss. How is loss of love like a war game or war? For one, there is the question of guilt. In the opening poem, Stone associates her own pain with that of a soldier she converses with: “I weep to her. / I’ve lost who I thought I loved and she says I did / this thing and to whom was that child beloved” (ix)? What has been done and cannot be undone?

Like the playing of one character continually in the games, hurt reverberates, is difficult to stop returning to, repeating. As Stone writers, “Living the role is like if you listen to a song and it was your song with your girl — / your brain tells you to stop you can’t stop” (32). And how to tell what is real and should one have to if, at times, it pleases? The speaker references the ex-lover’s face “here or here and here / and lit / and dark” (7). And certainly, the loss of love can resemble a death, as “Love Poem,” shared here in its entirety, may imply:

Undo the next time beauty

turns into tenderness turns

into a killing (25)

The cover of Stone’s book is an image by Adam Fuss called “Love.” It depicts “two eviscerated rabbits on a photosensitized sheet of paper,” exposed to light. The photograph is horrible, chilling and also gorgeous, the rabbit organs glowing with an array of yellows, reds, and blues, the entrails in compelling shapes and patterns. The title of the image (as it relates to the content) and the impetus behind Kill Class resonate: even violence and trauma deserve our attention and our art (which is love). Judgement is not the point nor is looking away possible. Horror, even simulated, holds truth.

Visit Tupelo Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.