ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Josie Moore is a writer, an artist, and a philosopher living in the south-west of England. Her interests coalesce around the intersection of the poetic and the political, with a particular emphasis on process, relationality, ethics, words, and flowers. Her future plans include dismantling capitalism and co-creating a more beautiful world, with and for others.

August 21, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

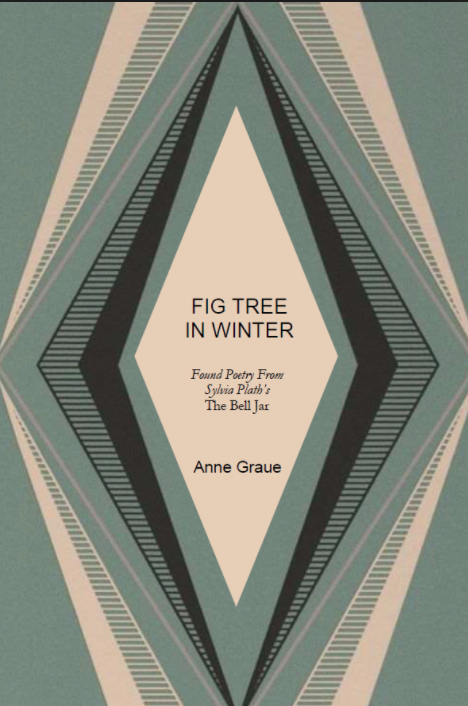

Review of Fig Tree in Winter by Anne Graue

Fig Tree in Winter

by Anne Graue

Dancing Girl Press, 2017

It is a brave endeavour, to make poetry from poetry; and yet that is what Anne Graue has done with Fig Tree in Winter (Dancing Girl Press, 2017). The source material is The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath’s infamous autobiographical novel — published just a month before her death in 1963, the book recounts her first breakdown, ten years prior. Graue takes her title from a passage where Esther, the ‘I’/eye of the text, captivated by the image of a fig-tree in a short story she’s read (“in winter under the snow and then…in spring with all the green fruit”), imagines all her potential futures branching off, like a tree bearing ripe figs, ready for plucking. Overwhelmed by choice, unable to select just one path, one fig, she watches them shrivel and fall to the ground — she pictures herself “starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind.” Esther’s imagined tree, unlike the fig-tree in the story (and unlike biological fig-trees), does not offer the redemption of spring: the fruit, once fallen, will not return. In this figgy cosmology, a winter tree bears no fruit — and thus, no future.

Plath was, of course, a poet first and foremost. In many ways, The Bell Jar is a poem — its structure, its clarity and precision of expression, its repeated themes (many echoed in her Ariel poems) surging up from some chthonic underspace. And the point-of-view: the text gives us Plath looking backward toward her younger self looking forward toward a future that she — poet, writer, mother, wife — now inhabits. The events of the book, then, are implicitly apprehended by both author and reader through the lens of the life the author would go on to live. There is a scene near the end, when Esther’s once-fiancé says, “I wonder who you’ll marry now,” which is exquisitely heartbreaking to read precisely because one knows who Sylvia married, and one senses (accurately or otherwise) that Sylvia felt this too, when she was writing. Her figs all withering on the ground: the Sylvia who wrote this was yet to receive much recognition or acclaim for her work; The Bell Jar itself would be rejected by her US publisher, and as for her marriage, her future — — — . This melancholy undercurrent, this choreography of memory around something dark and sad and unspoken, lends the book much of its poetic quality. One could even argue that The Bell Jar is itself a work of found poetry, co-created by reader and author from the narrative of Plath’s own brief-flaming deep-felt life. The notion of generating and distilling new poetry from this rich terrain, then, is an intriguing one. And when I open the chapbook, as if by magic or in response, I am met with a question: ‘Do you Know what a Poem is?’

The poems found in Fig Tree in Winter do not lay bare their roots, the traces of their source. Rather than present us with erasures, or even direct references, Graue pieces and stitches, a word here, an image there. As a result, the poems have a sort of self-sufficiency: they arise from but do not depend upon the original text. Graue’s process draws out and weaves together images and themes, which coalesce delicately with the hazy (un)logic of a lucid dream. Bathtubs and graves merge and echo; fingers are charmed open by the moon; bouquets of dying flowers are offered up with sacred simplicity. An extravagant feast, laid out in (and on a) ‘Banquet Table’, seems to melt and run into one incomprehensible mixture. These are liminal pieces: a poetry of the edges of things: the blurring-points where self dissolves into other, into ether.

The effect is one of distillation — of purity — of being in the presence of something essential and resonant. Resonant, reverent: again that sense of sacred simplicity. These small poems expand within me, creating quiet space in amidst the maddened whirl and swirl and everythingness of the world. They remind me, in some ways, of Plath’s Ariel poems; but there is a seedling-small sense of hope, too. There is engagement with place, with situation — “the shivering woods / topography, the / llandscape — a sense, perhaps, of waiting, of being behind glass, but not the distorting hall-of-mirrors glass of Plath’s bell jar. The crystalline ‘Cocoon’ skilfully and sparely employs the most ordinary of language to build a soft and winterlit world that is tangible in its safety: bright blanket as momentary defence against the darkness of things. And that, I think, is the hope-seed I can see. The dormant fig-tree, wintering, stark and stripped in the dark of the year, bears no fruit. But somewhere deep, the sap is moving — life is stirring — possibilities are ripening. And what a necessary tonic this hope is! Poetry that reminds me, yes, the darkness is (this is a world of executions, of senselessness, of cadavers, a world where all too often “something awful happen[s]”); but the darkness is not all that is. The fig-tree may be “lonely under the snow”, but perhaps that snow is a winter blanket, a cocoon: not the silence of death, but the quiet of restoration, of recovery, of renewal.

Perhaps, perhaps.

I do not — cannot — know what these poems mean.

I do not — cannot — know what a poem is.

But I can say that maybe sometimes a poem is a thing that haunts. Something that moves through my blood, that sings in my heartbeat, that makes the world more luminous, more truthful. That calls me towards meaning, towards reflection, even as it confounds me. The clarity — and the unknowableness — of a winter tree.

Visit Dancing Girl Press' Website

Fig Tree in Winter

by Anne Graue

Dancing Girl Press, 2017

It is a brave endeavour, to make poetry from poetry; and yet that is what Anne Graue has done with Fig Tree in Winter (Dancing Girl Press, 2017). The source material is The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath’s infamous autobiographical novel — published just a month before her death in 1963, the book recounts her first breakdown, ten years prior. Graue takes her title from a passage where Esther, the ‘I’/eye of the text, captivated by the image of a fig-tree in a short story she’s read (“in winter under the snow and then…in spring with all the green fruit”), imagines all her potential futures branching off, like a tree bearing ripe figs, ready for plucking. Overwhelmed by choice, unable to select just one path, one fig, she watches them shrivel and fall to the ground — she pictures herself “starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind.” Esther’s imagined tree, unlike the fig-tree in the story (and unlike biological fig-trees), does not offer the redemption of spring: the fruit, once fallen, will not return. In this figgy cosmology, a winter tree bears no fruit — and thus, no future.

Plath was, of course, a poet first and foremost. In many ways, The Bell Jar is a poem — its structure, its clarity and precision of expression, its repeated themes (many echoed in her Ariel poems) surging up from some chthonic underspace. And the point-of-view: the text gives us Plath looking backward toward her younger self looking forward toward a future that she — poet, writer, mother, wife — now inhabits. The events of the book, then, are implicitly apprehended by both author and reader through the lens of the life the author would go on to live. There is a scene near the end, when Esther’s once-fiancé says, “I wonder who you’ll marry now,” which is exquisitely heartbreaking to read precisely because one knows who Sylvia married, and one senses (accurately or otherwise) that Sylvia felt this too, when she was writing. Her figs all withering on the ground: the Sylvia who wrote this was yet to receive much recognition or acclaim for her work; The Bell Jar itself would be rejected by her US publisher, and as for her marriage, her future — — — . This melancholy undercurrent, this choreography of memory around something dark and sad and unspoken, lends the book much of its poetic quality. One could even argue that The Bell Jar is itself a work of found poetry, co-created by reader and author from the narrative of Plath’s own brief-flaming deep-felt life. The notion of generating and distilling new poetry from this rich terrain, then, is an intriguing one. And when I open the chapbook, as if by magic or in response, I am met with a question: ‘Do you Know what a Poem is?’

The poems found in Fig Tree in Winter do not lay bare their roots, the traces of their source. Rather than present us with erasures, or even direct references, Graue pieces and stitches, a word here, an image there. As a result, the poems have a sort of self-sufficiency: they arise from but do not depend upon the original text. Graue’s process draws out and weaves together images and themes, which coalesce delicately with the hazy (un)logic of a lucid dream. Bathtubs and graves merge and echo; fingers are charmed open by the moon; bouquets of dying flowers are offered up with sacred simplicity. An extravagant feast, laid out in (and on a) ‘Banquet Table’, seems to melt and run into one incomprehensible mixture. These are liminal pieces: a poetry of the edges of things: the blurring-points where self dissolves into other, into ether.

The effect is one of distillation — of purity — of being in the presence of something essential and resonant. Resonant, reverent: again that sense of sacred simplicity. These small poems expand within me, creating quiet space in amidst the maddened whirl and swirl and everythingness of the world. They remind me, in some ways, of Plath’s Ariel poems; but there is a seedling-small sense of hope, too. There is engagement with place, with situation — “the shivering woods / topography, the / llandscape — a sense, perhaps, of waiting, of being behind glass, but not the distorting hall-of-mirrors glass of Plath’s bell jar. The crystalline ‘Cocoon’ skilfully and sparely employs the most ordinary of language to build a soft and winterlit world that is tangible in its safety: bright blanket as momentary defence against the darkness of things. And that, I think, is the hope-seed I can see. The dormant fig-tree, wintering, stark and stripped in the dark of the year, bears no fruit. But somewhere deep, the sap is moving — life is stirring — possibilities are ripening. And what a necessary tonic this hope is! Poetry that reminds me, yes, the darkness is (this is a world of executions, of senselessness, of cadavers, a world where all too often “something awful happen[s]”); but the darkness is not all that is. The fig-tree may be “lonely under the snow”, but perhaps that snow is a winter blanket, a cocoon: not the silence of death, but the quiet of restoration, of recovery, of renewal.

Perhaps, perhaps.

I do not — cannot — know what these poems mean.

I do not — cannot — know what a poem is.

But I can say that maybe sometimes a poem is a thing that haunts. Something that moves through my blood, that sings in my heartbeat, that makes the world more luminous, more truthful. That calls me towards meaning, towards reflection, even as it confounds me. The clarity — and the unknowableness — of a winter tree.

Visit Dancing Girl Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.