ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Anna Press is a writer and educator living in Brooklyn, NY, with her husband and three rebellious dachshunds. She writes reviews, essays, short stories, the occasional poem — and is currently working on a novel. Talk to her on Twitter, where her handle is @annaepress.

April 4, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Review of His Strange Boy Eve by Eric Cline

His Strange Boy Eve

by Eric Cline

Yellow Chair Press, 2016

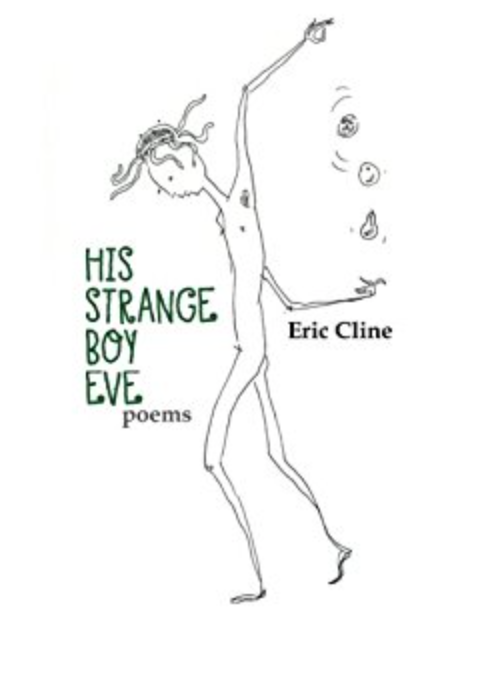

Upon my second read of Eric Cline’s His Strange Boy Eve, I noticed that the cover illustration would not be out of place among the drawings on and in Shel Silverstein’s books — fine, sketchy line art that is not inaccessible to children, but that carries sadness, humor, irony, and other weightier feelings to adults.

Cline’s first poem, appropriately, opens with a queer revision of Genesis and the fall from grace. In “i am not religious but,” the speaker re-imagines the story of Adam and Eve, “two adams: two queer — two faggots — two me’s,” one grown from the other’s rib. Their Eden, in Cline’s retelling, is not one of shame and fig leaves, but one where sex occurs “exactly / as god had intended,” pragmatic and a little cheeky. After a natural and vigorous romp, one adam wakes and bites into the apple — this part of the story is no different. Cline writes, “the fruit tasted himself for the / first time, and faggots were loved for the last,” subverting the idea that knowledge is shame. Deviating from the idea of original sin as bound to one gender, deviating from the idea of original sin in general, and suggesting lack of love as the reason humankind was cast out from Eden is a lot to pack into this short piece, but a powerful start to the collection. The rewriting of a familiar tale feels like more than a counternarrative, a translation of a different kind.

One of my favorite poems, “inherited sin,” seems to be almost in conversation with “two adams.” Balancing queerness against Eve’s rebellion, the speaker is “the rib / of her rib,” to their mother, a soul running parallel. They both “love / the snake with his promises,” both acutely aware of their wombs, “hers / authentic. mine / something like / a wax apple.” Like a wax casting and a subtle allusion to forbidden fruit and the one who takes knowledge and control:

neither of us

loves the man who

tells us where we

cannot go. no,

both of us tasted

rebellion. her teeth just

grazed the peel first.

Playing off of this tension between known and retold, normal and different, Cline’s poems zoom in and out in their investigation of queerness. Poems like “when the straight kids first suspected we were different,” and “years” take almost a bird’s-eye retrospective of young, formative experiences. The former opens situated in the strange injustices of elementary school — untaken seats that are not open, the mystery of multiplication not mysterious enough to disguise what is plain. Fortune tellers, the feeling of shrinking as others grow big. “Eventually,” Cline writes, pulling back from these grounding and familiar details, “some of us found / our way back to shore and sanity. eventually, / some of us drowned.” These paths seem equally likely, almost random, like the only two forks in an ambiguous road. In “years,” a list poem, Cline guides the reader from birth through young adulthood in a blur of memories — telling moments, perhaps, rather than highlights. All are memories of the poet’s life except one; Anaiis Nin quoted at thirteen years into the timeline, “and the day came when the risk to remain / tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom,” a moment that feels uncannily like reading your old diaries and remembering the discovery of something that made you recognize yourself, and, painfully, wincingly, is bookended by comments from a boy named Matthew, who at twelve says, “i like you too, man,” and at fourteen, proclaims, “eric cline is a faggot.” Um, well, fuck you, Matthew.

Within the framework of these variations on storytelling, other significant themes and patterns emerge. In “jellyfish man” and “genderqueer,” there is some delightful, eerie, weird, primordial fish language, as I’ve been calling it in my head — it feels like placing of oneself on a cold glass slide under a microscope and interpreting life in the magnified sights. “jellyfish man,” a kind of love poem, flows through short lovely vignettes, some, like the following, more concrete than others:

before a jellyfish

larva becomes a full-

grown drifter it first

attaches to a solid

surface, usually a rock

or some such thing but

you

were the strongest

thing in my eyeless

line of sight and for

that i loved you

instantly

The way the stanzas bookend the you compels the reader to visually see the “you” as this strong, standalone entity, introduced by impassive, conversational language — the likes of which one might hear in a Blue Planet documentary — and followed by such an earnest, almost mournful confession. It’s jarring, in an exciting way.

“genderqueer” depicts desire a little differently; sex is like “a shrimp’s shell you peel before piercing krill / with your teeth —” and genitals are a reality at odds with an urge to “evolve” from something like “the cursed urchin between my legs,” to “an amoeba, no cock or clit, just / cells / dividing into themselves.”

i want to be peeled and have my outsides placed

to the side, where they belong.

Has anyone not felt that way, at one time or another?

Problems and questions of the body, sex, and love filter through the rest of the collection, resurfacing and changing in poems like “herald.” Here, unrequited desire is framed through mostly floral, natural imagery, but begins with the water, a thoughtful conclusion of what I so unceremoniously think of as fish language. “it begins / as an ebb / in my chest,” the speaker writes, proceeding to describe “a message / from across the sea / of green carnations,” which bleeds into, as Cline does so well, familiar images deconstructed and re-contextualized. “he’ll / love me not / regardless of how / many petals i / pull off my sadly / cocked stalk,” the speaker observes, determining, “only / girls’ flower petals / are right for / the picking.”

While the poems are strong on their own, the way Cline braids these threads of biblical imagery, fish language, and love with the body in abstract space as well as viscerally real places makes the collection speak on a deeper level. It ends with a nod to where it begins, in “where were you when i laid the earth’s foundation?” Speaking to a you that is perhaps god but not god, and somewhat reminiscent of the powerful you in “jellyfish man,” the speaker writes, and one thinks of the flaming sword at the gates of the garden of Eden, “i went to the burning bush / and heard you.” Would that we could all confront so readily, hear what we need to hear.

Visit Eric Cline's website

His Strange Boy Eve

by Eric Cline

Yellow Chair Press, 2016

Upon my second read of Eric Cline’s His Strange Boy Eve, I noticed that the cover illustration would not be out of place among the drawings on and in Shel Silverstein’s books — fine, sketchy line art that is not inaccessible to children, but that carries sadness, humor, irony, and other weightier feelings to adults.

Cline’s first poem, appropriately, opens with a queer revision of Genesis and the fall from grace. In “i am not religious but,” the speaker re-imagines the story of Adam and Eve, “two adams: two queer — two faggots — two me’s,” one grown from the other’s rib. Their Eden, in Cline’s retelling, is not one of shame and fig leaves, but one where sex occurs “exactly / as god had intended,” pragmatic and a little cheeky. After a natural and vigorous romp, one adam wakes and bites into the apple — this part of the story is no different. Cline writes, “the fruit tasted himself for the / first time, and faggots were loved for the last,” subverting the idea that knowledge is shame. Deviating from the idea of original sin as bound to one gender, deviating from the idea of original sin in general, and suggesting lack of love as the reason humankind was cast out from Eden is a lot to pack into this short piece, but a powerful start to the collection. The rewriting of a familiar tale feels like more than a counternarrative, a translation of a different kind.

One of my favorite poems, “inherited sin,” seems to be almost in conversation with “two adams.” Balancing queerness against Eve’s rebellion, the speaker is “the rib / of her rib,” to their mother, a soul running parallel. They both “love / the snake with his promises,” both acutely aware of their wombs, “hers / authentic. mine / something like / a wax apple.” Like a wax casting and a subtle allusion to forbidden fruit and the one who takes knowledge and control:

neither of us

loves the man who

tells us where we

cannot go. no,

both of us tasted

rebellion. her teeth just

grazed the peel first.

Playing off of this tension between known and retold, normal and different, Cline’s poems zoom in and out in their investigation of queerness. Poems like “when the straight kids first suspected we were different,” and “years” take almost a bird’s-eye retrospective of young, formative experiences. The former opens situated in the strange injustices of elementary school — untaken seats that are not open, the mystery of multiplication not mysterious enough to disguise what is plain. Fortune tellers, the feeling of shrinking as others grow big. “Eventually,” Cline writes, pulling back from these grounding and familiar details, “some of us found / our way back to shore and sanity. eventually, / some of us drowned.” These paths seem equally likely, almost random, like the only two forks in an ambiguous road. In “years,” a list poem, Cline guides the reader from birth through young adulthood in a blur of memories — telling moments, perhaps, rather than highlights. All are memories of the poet’s life except one; Anaiis Nin quoted at thirteen years into the timeline, “and the day came when the risk to remain / tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom,” a moment that feels uncannily like reading your old diaries and remembering the discovery of something that made you recognize yourself, and, painfully, wincingly, is bookended by comments from a boy named Matthew, who at twelve says, “i like you too, man,” and at fourteen, proclaims, “eric cline is a faggot.” Um, well, fuck you, Matthew.

Within the framework of these variations on storytelling, other significant themes and patterns emerge. In “jellyfish man” and “genderqueer,” there is some delightful, eerie, weird, primordial fish language, as I’ve been calling it in my head — it feels like placing of oneself on a cold glass slide under a microscope and interpreting life in the magnified sights. “jellyfish man,” a kind of love poem, flows through short lovely vignettes, some, like the following, more concrete than others:

before a jellyfish

larva becomes a full-

grown drifter it first

attaches to a solid

surface, usually a rock

or some such thing but

you

were the strongest

thing in my eyeless

line of sight and for

that i loved you

instantly

The way the stanzas bookend the you compels the reader to visually see the “you” as this strong, standalone entity, introduced by impassive, conversational language — the likes of which one might hear in a Blue Planet documentary — and followed by such an earnest, almost mournful confession. It’s jarring, in an exciting way.

“genderqueer” depicts desire a little differently; sex is like “a shrimp’s shell you peel before piercing krill / with your teeth —” and genitals are a reality at odds with an urge to “evolve” from something like “the cursed urchin between my legs,” to “an amoeba, no cock or clit, just / cells / dividing into themselves.”

i want to be peeled and have my outsides placed

to the side, where they belong.

Has anyone not felt that way, at one time or another?

Problems and questions of the body, sex, and love filter through the rest of the collection, resurfacing and changing in poems like “herald.” Here, unrequited desire is framed through mostly floral, natural imagery, but begins with the water, a thoughtful conclusion of what I so unceremoniously think of as fish language. “it begins / as an ebb / in my chest,” the speaker writes, proceeding to describe “a message / from across the sea / of green carnations,” which bleeds into, as Cline does so well, familiar images deconstructed and re-contextualized. “he’ll / love me not / regardless of how / many petals i / pull off my sadly / cocked stalk,” the speaker observes, determining, “only / girls’ flower petals / are right for / the picking.”

While the poems are strong on their own, the way Cline braids these threads of biblical imagery, fish language, and love with the body in abstract space as well as viscerally real places makes the collection speak on a deeper level. It ends with a nod to where it begins, in “where were you when i laid the earth’s foundation?” Speaking to a you that is perhaps god but not god, and somewhat reminiscent of the powerful you in “jellyfish man,” the speaker writes, and one thinks of the flaming sword at the gates of the garden of Eden, “i went to the burning bush / and heard you.” Would that we could all confront so readily, hear what we need to hear.

Visit Eric Cline's website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.