ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Jennifer Saunders is a poet living in German-speaking Switzerland. Her chapbook Self-Portrait with Housewife was selected by Gail Wronsky as the winner of the 2017 Clockwise chapbook contest and will be published by Tebot Bach Press in Spring 2018. Her poems and reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, Dunes Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Pittsburgh Poetry Review, Spillway, Stirring: A Literary Collection, ucity review, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from Pacific University and in the winters she teaches skating in a hockey school.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

Note Pinned to My Lips

February 27, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

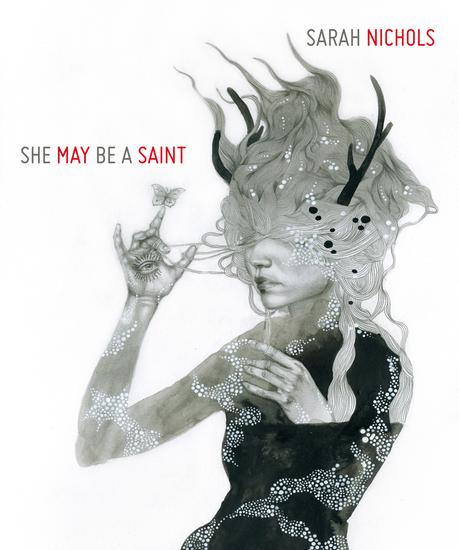

Review of She May Be A Saint by Sarah Nichols

She May Be A Saint

by Sarah Nichols

Hermeneutic Chaos Press, 2016

In her chapbook She May Be A Saint, Sarah Nichols uses the works of C.D. Wright and Sylvia Plath to create poems of extinction and becoming. As I read this collection of centos I found myself wondering if the voice in these poems is seeking to rid herself of identity or if she is struggling to be born. This tension is established immediately in the opening lines of the first poem, "Once I Was":

Call me the

Duchess of nothing.

I came to be

identified with it.

With these lines the speaker introduces the idea of her erasure and at the same time firmly establishes her selfhood — though the language speaks of nothingness, the tone is confident and assertive, issuing a directive ("Call me") in a clear first person identity. This is not a voice of nothing, yet this same poem closes on an expression of shedding the self with the lines "Words to rid me / of // me." Even the very form of the chapbook, composed as it is of centos, enacts this tension between erasure and creation by using pre-existing poetic works (the speaker masking herself behind the words of another) to create entirely new poems that exist as their own art form independent of the source materials (the speaker forging a new, singular identity).

A transformation unfolds throughout this collection. In the poem "In Bloom" we see clearly both the shedding and the becoming:

Gestures flake off - -

the dark of the

body

is in

bloom.

In order for a new or authentic self to emerge, the old one must be broken off, chipped away. The diction of this poem — threaded with words like "fears," "blasted," and "dark" — reminds us that the process of emergence, however welcome, can also be painful; the short lines and stanzas create a sense of resistance as if, watching her own becoming, the speaker is a bit frightened of her gathering power.

This sense of erasure preceding creation weaves its way through these poems, many of which refer simultaneously to emptiness and bodies. For example, the title poem speaks of

[m]y share of

harmful bodies,

a disturbance

of emptiness.

And in "I Would Open" the speaker is both "as frail / as smoke" and "expansive" while the title harkens back to "In Bloom" and the process of opening, blooming, becoming. In the poem "Mask Increases," too, there is both body (albeit "a / doll's body") and "absence," "darkness;" while in "No Shadow" erasure and existence appear again side-by-side. That poem opens with an image of obliteration:

I let her go. As

if I had

exposed

some film

to sun.

Such an act would literally destroy whatever image had been captured on the film, yet the speaker finds herself again — and then again immediately enacts an erasure by calling herself "an unidentified woman. // You will scarcely remember." In "Myself Again" "The body does not / come into it at all." When the body does enter this poem it is "a suspect" and the speaker seeks to "efface it."

This push-and-pull between a sort of disappearing or non-existence and a sense of becoming creates a tension, as if the speaker does not fully welcome this process of change. The short lines and stanzas contribute to this feeling, as in the poem "Invisible Wounds" with the lines

The first time it happened,

I was

wounded into

dormancy.

Seamless.

The line "[t]he first time it happened" comes out easily because it carries no risk for the speaker, there is no emotional information in this phrase. As soon as the poem shifts to the first person, to the impact whatever "it" was had on the speaker, the lines become truncated to mimic the difficulty of expression. "I was" exists as a complete stanza as if the speaker needed to gather herself before moving on to utter the word "wounded."

"Experiences, quietly humming" is the longest poem in the book and serves as an emotional turning point. On some readings I read the lines "I was supposed to be a / virgin" quite literally as a memory of an abuse. There is menace in the lines

I am

the magician's

girl

who

does not flinch.

She is so sweet

in a blackout

of knives.

Other times I read this poem more allegorically — most female saints, after all, were expected to be virgins (one thinks of the virgin-martyrs Saint Agatha, Saint Agnes, and Saint Lucy) and so this saint, too, is "supposed to be a / virgin." When the body enters this poem it is "lion-red" with "wings of glass" — a mythical creature

more terrible

than

she ever was

the

terriblest part

upon release.

With this release the creation of the new self is complete, and this reaffirmed in the next poem in the collection, "Other Bodies," with its closing lines "a body, / flickering. // My new instrument."

In spite of their physical concision on the page, these centos enact an expansive transformation and creation of self. It is not a gentle process (obtaining sainthood rarely is), and these poems are full of images reflecting the pain of transformation (the body as a "blasted coil"; "unmendable"; "sucked and burned"; "a red tatter"). Yet the voice in She May Be A Saint speaks with power and confidence and claims her new self, her "new instrument" "terrible — upon release." Perhaps there is no conflict in these poems between the shedding of identity and the emergence of self. Perhaps, in the end, for a woman to shed her identity is to be born new.

She May Be A Saint

by Sarah Nichols

Hermeneutic Chaos Press, 2016

In her chapbook She May Be A Saint, Sarah Nichols uses the works of C.D. Wright and Sylvia Plath to create poems of extinction and becoming. As I read this collection of centos I found myself wondering if the voice in these poems is seeking to rid herself of identity or if she is struggling to be born. This tension is established immediately in the opening lines of the first poem, "Once I Was":

Call me the

Duchess of nothing.

I came to be

identified with it.

With these lines the speaker introduces the idea of her erasure and at the same time firmly establishes her selfhood — though the language speaks of nothingness, the tone is confident and assertive, issuing a directive ("Call me") in a clear first person identity. This is not a voice of nothing, yet this same poem closes on an expression of shedding the self with the lines "Words to rid me / of // me." Even the very form of the chapbook, composed as it is of centos, enacts this tension between erasure and creation by using pre-existing poetic works (the speaker masking herself behind the words of another) to create entirely new poems that exist as their own art form independent of the source materials (the speaker forging a new, singular identity).

A transformation unfolds throughout this collection. In the poem "In Bloom" we see clearly both the shedding and the becoming:

Gestures flake off - -

the dark of the

body

is in

bloom.

In order for a new or authentic self to emerge, the old one must be broken off, chipped away. The diction of this poem — threaded with words like "fears," "blasted," and "dark" — reminds us that the process of emergence, however welcome, can also be painful; the short lines and stanzas create a sense of resistance as if, watching her own becoming, the speaker is a bit frightened of her gathering power.

This sense of erasure preceding creation weaves its way through these poems, many of which refer simultaneously to emptiness and bodies. For example, the title poem speaks of

[m]y share of

harmful bodies,

a disturbance

of emptiness.

And in "I Would Open" the speaker is both "as frail / as smoke" and "expansive" while the title harkens back to "In Bloom" and the process of opening, blooming, becoming. In the poem "Mask Increases," too, there is both body (albeit "a / doll's body") and "absence," "darkness;" while in "No Shadow" erasure and existence appear again side-by-side. That poem opens with an image of obliteration:

I let her go. As

if I had

exposed

some film

to sun.

Such an act would literally destroy whatever image had been captured on the film, yet the speaker finds herself again — and then again immediately enacts an erasure by calling herself "an unidentified woman. // You will scarcely remember." In "Myself Again" "The body does not / come into it at all." When the body does enter this poem it is "a suspect" and the speaker seeks to "efface it."

This push-and-pull between a sort of disappearing or non-existence and a sense of becoming creates a tension, as if the speaker does not fully welcome this process of change. The short lines and stanzas contribute to this feeling, as in the poem "Invisible Wounds" with the lines

The first time it happened,

I was

wounded into

dormancy.

Seamless.

The line "[t]he first time it happened" comes out easily because it carries no risk for the speaker, there is no emotional information in this phrase. As soon as the poem shifts to the first person, to the impact whatever "it" was had on the speaker, the lines become truncated to mimic the difficulty of expression. "I was" exists as a complete stanza as if the speaker needed to gather herself before moving on to utter the word "wounded."

"Experiences, quietly humming" is the longest poem in the book and serves as an emotional turning point. On some readings I read the lines "I was supposed to be a / virgin" quite literally as a memory of an abuse. There is menace in the lines

I am

the magician's

girl

who

does not flinch.

She is so sweet

in a blackout

of knives.

Other times I read this poem more allegorically — most female saints, after all, were expected to be virgins (one thinks of the virgin-martyrs Saint Agatha, Saint Agnes, and Saint Lucy) and so this saint, too, is "supposed to be a / virgin." When the body enters this poem it is "lion-red" with "wings of glass" — a mythical creature

more terrible

than

she ever was

the

terriblest part

upon release.

With this release the creation of the new self is complete, and this reaffirmed in the next poem in the collection, "Other Bodies," with its closing lines "a body, / flickering. // My new instrument."

In spite of their physical concision on the page, these centos enact an expansive transformation and creation of self. It is not a gentle process (obtaining sainthood rarely is), and these poems are full of images reflecting the pain of transformation (the body as a "blasted coil"; "unmendable"; "sucked and burned"; "a red tatter"). Yet the voice in She May Be A Saint speaks with power and confidence and claims her new self, her "new instrument" "terrible — upon release." Perhaps there is no conflict in these poems between the shedding of identity and the emergence of self. Perhaps, in the end, for a woman to shed her identity is to be born new.Note: Hermeneutic Chaos Press has been shut down for about a year now so this chapbook should be considered out of print. An electronic version of She May Be A Saint has been made available, though, through the Poetry Center Chapbook Exchange.

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.