ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Cody Stetzel received his MA in Creative Writing in poetry from the University of California at Davis. While from Rochester, New York, the former upstate & northeast hermit has replaced his slow-moving winter energies with the vitality of the west coast. His work has appeared in The East Coast Literary Review and Neovox: International.

December 28, 2017

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

And We Made Magic: Review of Afterwards by Amy Bartlett

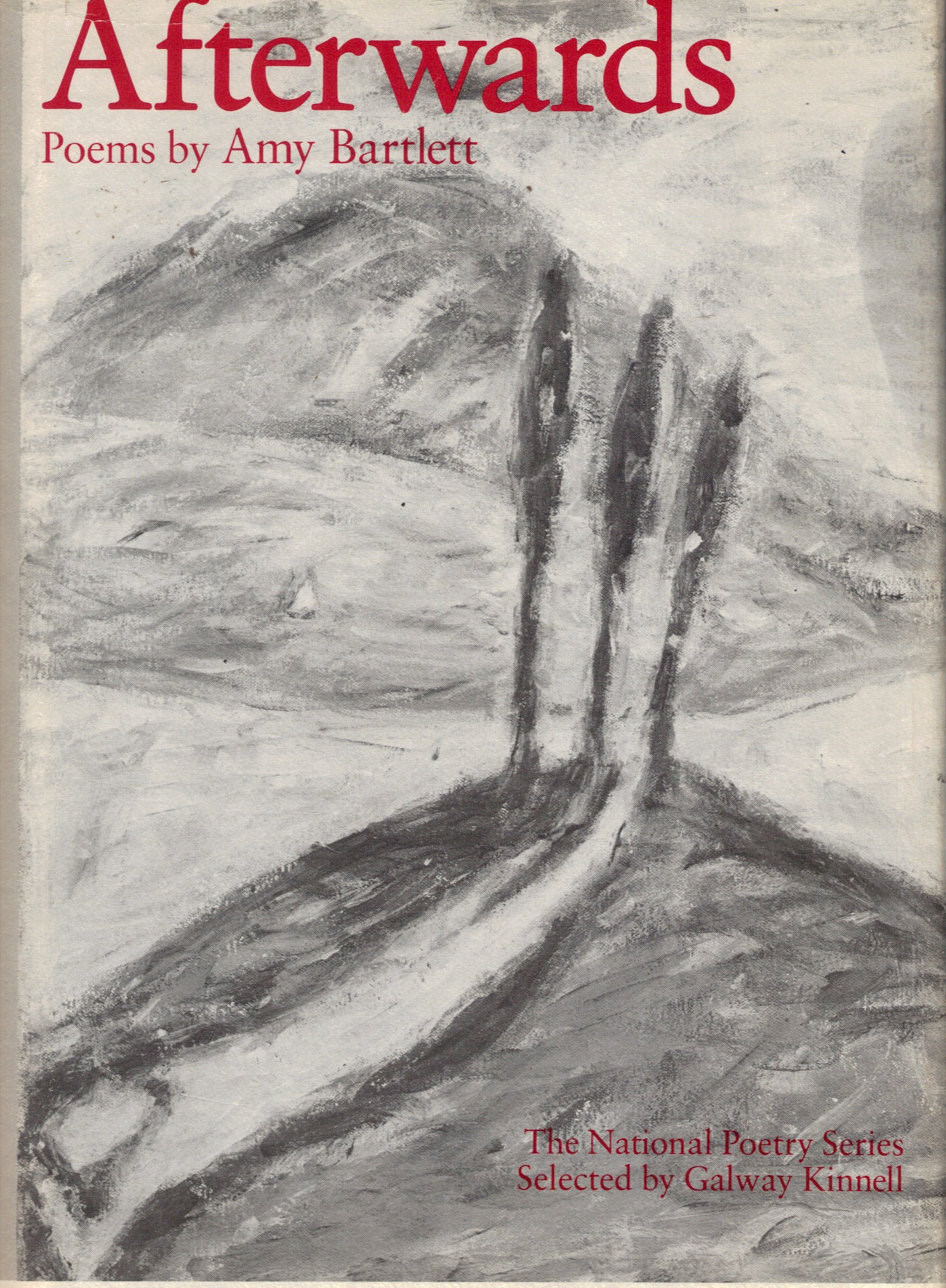

Afterwards

by Amy Bartlett

Persea Books, 1985

I'm one of those people with a poetry education. It wasn't bad for me, in fact I truly appreciated my time within my writing program; however, I can't deny that much of this time was spent hounding against things like nostalgia, and childhood. Reading Afterwards (Persea Books, 1985) was particularly evocative for me; it felt as though I was re-learning to encounter the world, that there can be poetry in the past so long as it isn't a simple effacement of desire; instead is a thinking and an understanding that the memory isn't entirely your enemy. It took me three reads. I wasn't sure about it, but I wanted to be.

Everywhere I've looked regarding this book I read descriptions like "soft," "quiet," or "gentle" — how lame. I think to label this book "soft," "quiet," or "gentle," is a blasé way of saying I think this book is weak, or, this book does not set to capture grandiose ideas and therefore is not fully poetic. This is not to say that describing a work of poetry or art as "soft," "quiet," or "gentle," is always a diminishment; but, instead, to offer that in this particular case, I feel that those words do not work as hard as one would need them to work to detail the treasures that Afterwards maps out for us.

What if: you invoked the ultra-personal; made statements that might otherwise seems cliché, contrite, counter-revolutionary; pursued and hounded not-interpretation, but nostalgia?

I offer the following Bartlett poem in full, to give an idea of what I mean:

Gypsy Moths

After dark, my father paints a band of tar

around each tree. "They’re bad this year."

A grandchild and now his son-in-law are gone.

As he angles his broom toward the high eaten branches,

I wonder if he sees my sister, patient, stationary,

her life that fragile and intricate.

When I read "Gypsy Moths," I read a poem witnessing an individual encountering loss. Isn't that such a poet move? To talk about loss by witnessing it in another? But my question for this poem is to whom does loss belong? Sister, father, grandchild? Or all of them? Perhaps that's the poetic being approached here — that one may watch another find loss in their labors, their rituals; however, be surrounded by the loss of others all around them at the same time. And furthermore, the progression of the verbs in this poem dictate, to me, the ongoingness of the speaker's loss: it does not offer the uncomplicated and immediate pain of having happened and ending; no, it demonstrates that loss is continual, and may be found so long as one has the means to notice it.

I find it takes a tremendous strength to write honestly about fragility. I think of Rilke in his Duino Elegies, specifically from "The Fourth Elegy," "We do not know the contours / of feeling, only what forms it from outside. / Who has not sat, scared, before his heart's curtain?" In my interpretation of Rilke's elegies, he is writing among the striations of vulnerability and ruin to find love's interstices. In my interpretation of Bartlett's Afterwards, she is writing among the foundations of structure and stability to find life's woundedness.

The poetic enchantment for this book seems to be in the appeal of both submitting to domestic role, and knowing better than to submit at all. Bartlett writes about children and childhood, domesticity and fantasy, living and dying, family and romance, and with the circling of a colorless pencil over the shading of a colored piece, blends her work together in an overlap and infiltration of majesty.

Visit Persea Books' Website

Afterwards

by Amy Bartlett

Persea Books, 1985

I'm one of those people with a poetry education. It wasn't bad for me, in fact I truly appreciated my time within my writing program; however, I can't deny that much of this time was spent hounding against things like nostalgia, and childhood. Reading Afterwards (Persea Books, 1985) was particularly evocative for me; it felt as though I was re-learning to encounter the world, that there can be poetry in the past so long as it isn't a simple effacement of desire; instead is a thinking and an understanding that the memory isn't entirely your enemy. It took me three reads. I wasn't sure about it, but I wanted to be.

Everywhere I've looked regarding this book I read descriptions like "soft," "quiet," or "gentle" — how lame. I think to label this book "soft," "quiet," or "gentle," is a blasé way of saying I think this book is weak, or, this book does not set to capture grandiose ideas and therefore is not fully poetic. This is not to say that describing a work of poetry or art as "soft," "quiet," or "gentle," is always a diminishment; but, instead, to offer that in this particular case, I feel that those words do not work as hard as one would need them to work to detail the treasures that Afterwards maps out for us.

What if: you invoked the ultra-personal; made statements that might otherwise seems cliché, contrite, counter-revolutionary; pursued and hounded not-interpretation, but nostalgia?

I offer the following Bartlett poem in full, to give an idea of what I mean:

Gypsy Moths

After dark, my father paints a band of tar

around each tree. "They’re bad this year."

A grandchild and now his son-in-law are gone.

As he angles his broom toward the high eaten branches,

I wonder if he sees my sister, patient, stationary,

her life that fragile and intricate.

When I read "Gypsy Moths," I read a poem witnessing an individual encountering loss. Isn't that such a poet move? To talk about loss by witnessing it in another? But my question for this poem is to whom does loss belong? Sister, father, grandchild? Or all of them? Perhaps that's the poetic being approached here — that one may watch another find loss in their labors, their rituals; however, be surrounded by the loss of others all around them at the same time. And furthermore, the progression of the verbs in this poem dictate, to me, the ongoingness of the speaker's loss: it does not offer the uncomplicated and immediate pain of having happened and ending; no, it demonstrates that loss is continual, and may be found so long as one has the means to notice it.

I find it takes a tremendous strength to write honestly about fragility. I think of Rilke in his Duino Elegies, specifically from "The Fourth Elegy," "We do not know the contours / of feeling, only what forms it from outside. / Who has not sat, scared, before his heart's curtain?" In my interpretation of Rilke's elegies, he is writing among the striations of vulnerability and ruin to find love's interstices. In my interpretation of Bartlett's Afterwards, she is writing among the foundations of structure and stability to find life's woundedness.

The poetic enchantment for this book seems to be in the appeal of both submitting to domestic role, and knowing better than to submit at all. Bartlett writes about children and childhood, domesticity and fantasy, living and dying, family and romance, and with the circling of a colorless pencil over the shading of a colored piece, blends her work together in an overlap and infiltration of majesty.

Visit Persea Books' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.