ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Karen J. Weyant's prose and poetry has appeared in Briar Cliff Review, Chautauqua, Copper Nickel, Harpur Palate, Mud Season Review, River Styx, Storm Cellar, Tahoma Literary Review, and Whiskey Island. She is the author of two chapbooks, including Wearing Heels in the Rust Belt published by Main Street Rag. She is an Associate Professor of English at Jamestown Community College in Jamestown, New York. In her spare time, she explores the Rust Belt regions of Western New York and Northern Pennsylvania. Learn more at her website.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

The Summer I Stopped Catching Bees

February 8, 2018

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

#TBT Reviews Series

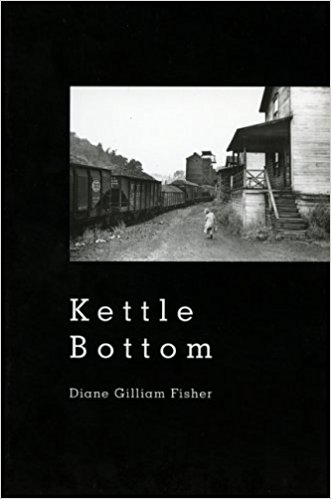

Review of Kettle Bottom by Diane Gilliam Fisher

Kettle Bottom

by Diane Gilliam Fisher

Perugia Press, 2004

For better or for worse, coal miners and the coal industry have recently been thrust into the limelight. I was born and raised in Pennsylvania and have a love of my state's history, especially its rugged, blue-collar history. Even though I didn't grow up in coal mining country, I have empathy for those who struggle to live in what is left in this world. Unfortunately, I often find that many people do not share my empathy. I want to tell them to forget the current politics. I want to tell them to forget what most contemporary media outlets are reporting. But what I really want to tell them is to read Kettle Bottom Diane Gilliam Fisher, perhaps one of the best poetry books ever written.

Kettle Bottom, published by Perugia Press in 2004, examines the years of 1920-21 in West Virginia, a period of tension and unrest in coal country. Divided into three sections, Fisher's collection intertwines a variety of voices, including wives, mine workers, and community children, all the while seeking to capture a time that is seemingly forgotten.

The first poem, "Explosion at Winco No. 9" acts as a preface to the rest of the book. In this poem, we are introduced to a coal miner's wife who recollects her friends' stories: "Delsey Salyer knowed Tom Junior by his toes/which his steel-toed boots had kept the fire off of" and "Betty Rose seen a piece of Willy's ear, the little/notched part where a hound had bit him/when he was a youn'un". At the end of the poem, we find out that this narrator is forced to identify her own husband by a patch of her own dress she had used to mend his clothes: "I seen a piece of my old blue dress/one of them bodies, blacked with smoke/but I could tell it was my patch up under the arm."

Already we hear the voice of someone who has witnessed the life and labors of coal miners. Already we know the feeling of dread in approaching recognizing and identifying the dead. Already, the tone has been set for the rest of the collection.

What follows is a myriad of work that explores different voices in a coal mining community. In one poem, "My Dearest Hazel," a friend writes to another about her relationship with her husband to caution her against marrying a miner, "I'm telling you, Hazel, for the sake of your own/sweet soul, when Clayton kisses me now/I don't taste nothing but coal." In another poem, "The Rocks Down Here", a miner seems to answer back to this thought as he seeks a sort of solace under the earth where a woman's eyes can't "follow after him, craving/to be somewhere else" and where she is not forced to "spend her days wiping coal dust/and scraping to feed young 'uns."

The second section of this book takes on a slightly different tone. This section, entitled "Raven Light" is a long poem made up of 15 sections depicting a young miner who is trapped underneath the ground. This poem acts as an interlude between the two other sections, as the narrator not only contemplates his current situation but also recounts memories of the past, especially those that focus on his own father who was killed in the coal mines.

The last section of the book brings the reader to the eruption of the tension in this community. Unlike the quiet contemplations found in the resigned voices in first section of the book, anger now rises to the surface. This anger is illustrated beginning in the first poem, when the company schoolteacher, watches from the sidelines. She describes in "Journal of Catherine Terry" the fury of a woman who has found out that members of her family have been killed in yet another mine disaster. Certainly, this grieving woman's emotions are not unusual, except for one action: she turns a dinner bucket upside down, which is a signal for the coal miners to go on strike.

What follows this poem are the voices that relay the anger, confusion, and yes, violence of these days. We learn that Baldwin-Felt agents, employed by the coal companies, arrive to take control of the situation, but then in an eruption of gunfire, many are left dead, along with a few members of the local community.

The violence only escalates more after that incident. In Fisher's poems, we hear from the coal miners themselves, especially those who are writing to loved ones outside the area, cautioning them not to believe everything they hear about their community. I find, however, that the anger is the most apparent through the observations of a child in the poem "A Reporter from New York Asks Edit Mae Chapman, Age Nine, What Her Daddy Tells Her about the Strike" where the child offers a litany of things they are not supposed to do including, "We ain't to talk to no dirtscum scabs/and we ain't to talk to God. My daddy/is very upset with the Lord."

Who eventually wins the strike? It's hard to tell. In the Author's Note found at the start of this book, we learn that Federal troops are dispatched to end the strike. Many of the miners, according to Fisher's note, were World War I veterans, and because of this, did not want to fight back against a group they knew so well. Thus, the strike ended and the miners returned to their homes. The good news is that the miners in this area were able to organize into unions. However, according to Fisher, the negotiations about working conditions "did little to better the lives of the miners and their families."

Yes, some who read this book may argue that the issues woven throughout this collection are no longer pertinent in today's world. We know more about working conditions in coal mines. We know more about the coal and its impact on both the natural environment and on us.

We just know more.

Still, I would argue that there are many things that haven't changed, including the world's perception of working-class rural people, and the economic disparities often found in blue collar jobs.

That's why this book should be read, again and again.

Visit Diane Gilliam Fisher's Poetry Foundation profile

Visit Perugia Press' Website

Kettle Bottom

by Diane Gilliam Fisher

Perugia Press, 2004

For better or for worse, coal miners and the coal industry have recently been thrust into the limelight. I was born and raised in Pennsylvania and have a love of my state's history, especially its rugged, blue-collar history. Even though I didn't grow up in coal mining country, I have empathy for those who struggle to live in what is left in this world. Unfortunately, I often find that many people do not share my empathy. I want to tell them to forget the current politics. I want to tell them to forget what most contemporary media outlets are reporting. But what I really want to tell them is to read Kettle Bottom Diane Gilliam Fisher, perhaps one of the best poetry books ever written.

Kettle Bottom, published by Perugia Press in 2004, examines the years of 1920-21 in West Virginia, a period of tension and unrest in coal country. Divided into three sections, Fisher's collection intertwines a variety of voices, including wives, mine workers, and community children, all the while seeking to capture a time that is seemingly forgotten.

The first poem, "Explosion at Winco No. 9" acts as a preface to the rest of the book. In this poem, we are introduced to a coal miner's wife who recollects her friends' stories: "Delsey Salyer knowed Tom Junior by his toes/which his steel-toed boots had kept the fire off of" and "Betty Rose seen a piece of Willy's ear, the little/notched part where a hound had bit him/when he was a youn'un". At the end of the poem, we find out that this narrator is forced to identify her own husband by a patch of her own dress she had used to mend his clothes: "I seen a piece of my old blue dress/one of them bodies, blacked with smoke/but I could tell it was my patch up under the arm."

Already we hear the voice of someone who has witnessed the life and labors of coal miners. Already we know the feeling of dread in approaching recognizing and identifying the dead. Already, the tone has been set for the rest of the collection.

What follows is a myriad of work that explores different voices in a coal mining community. In one poem, "My Dearest Hazel," a friend writes to another about her relationship with her husband to caution her against marrying a miner, "I'm telling you, Hazel, for the sake of your own/sweet soul, when Clayton kisses me now/I don't taste nothing but coal." In another poem, "The Rocks Down Here", a miner seems to answer back to this thought as he seeks a sort of solace under the earth where a woman's eyes can't "follow after him, craving/to be somewhere else" and where she is not forced to "spend her days wiping coal dust/and scraping to feed young 'uns."

The second section of this book takes on a slightly different tone. This section, entitled "Raven Light" is a long poem made up of 15 sections depicting a young miner who is trapped underneath the ground. This poem acts as an interlude between the two other sections, as the narrator not only contemplates his current situation but also recounts memories of the past, especially those that focus on his own father who was killed in the coal mines.

The last section of the book brings the reader to the eruption of the tension in this community. Unlike the quiet contemplations found in the resigned voices in first section of the book, anger now rises to the surface. This anger is illustrated beginning in the first poem, when the company schoolteacher, watches from the sidelines. She describes in "Journal of Catherine Terry" the fury of a woman who has found out that members of her family have been killed in yet another mine disaster. Certainly, this grieving woman's emotions are not unusual, except for one action: she turns a dinner bucket upside down, which is a signal for the coal miners to go on strike.

What follows this poem are the voices that relay the anger, confusion, and yes, violence of these days. We learn that Baldwin-Felt agents, employed by the coal companies, arrive to take control of the situation, but then in an eruption of gunfire, many are left dead, along with a few members of the local community.

The violence only escalates more after that incident. In Fisher's poems, we hear from the coal miners themselves, especially those who are writing to loved ones outside the area, cautioning them not to believe everything they hear about their community. I find, however, that the anger is the most apparent through the observations of a child in the poem "A Reporter from New York Asks Edit Mae Chapman, Age Nine, What Her Daddy Tells Her about the Strike" where the child offers a litany of things they are not supposed to do including, "We ain't to talk to no dirtscum scabs/and we ain't to talk to God. My daddy/is very upset with the Lord."

Who eventually wins the strike? It's hard to tell. In the Author's Note found at the start of this book, we learn that Federal troops are dispatched to end the strike. Many of the miners, according to Fisher's note, were World War I veterans, and because of this, did not want to fight back against a group they knew so well. Thus, the strike ended and the miners returned to their homes. The good news is that the miners in this area were able to organize into unions. However, according to Fisher, the negotiations about working conditions "did little to better the lives of the miners and their families."

Yes, some who read this book may argue that the issues woven throughout this collection are no longer pertinent in today's world. We know more about working conditions in coal mines. We know more about the coal and its impact on both the natural environment and on us.

We just know more.

Still, I would argue that there are many things that haven't changed, including the world's perception of working-class rural people, and the economic disparities often found in blue collar jobs.

That's why this book should be read, again and again.

Visit Diane Gilliam Fisher's Poetry Foundation profile

Visit Perugia Press' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.