ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick's work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Gulf Coast Journal, Salamander Magazine, The Texas Observer, The Missouri Review, Four Way Review, Harpur Palate, Passages North, among others. Hardwick serves as the poetry editor for The Boiler Journal.

March 1, 2022

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

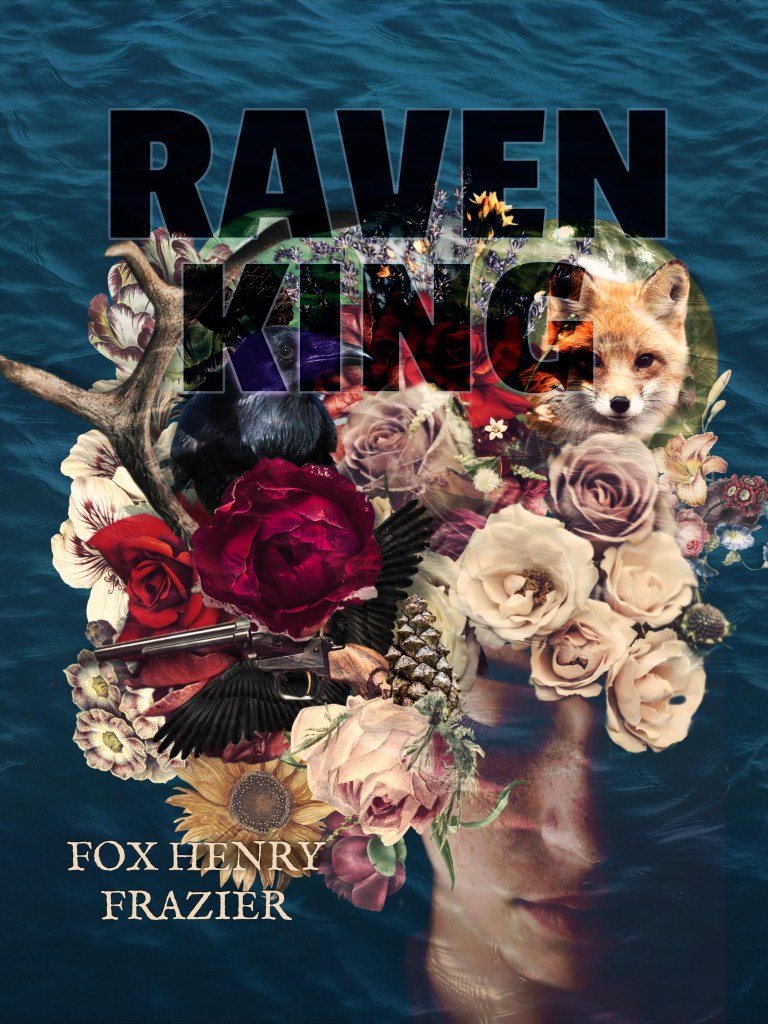

Review of Raven King by Fox Henry Frazier

Raven King

Fox Henry Frazier

YesPoetry Books, 2022

In a twist of roles, pulling at the tension of what is expected and flipping it on its head, Fox Henry Frazier's collection Raven King (YesPoetry Books, 2022) explores the doing and undoing of a myth. Moreover, in its destruction, a place is set for a rebirth. However, Frazier lingers within a myth born into—the Raven-Haired poems, which address the expectations on the female body, the ethos of violence, what is found repeated within childhood fairy tales. The Exodus poems address how to overcome before being buried and maintain a connection to the beauty and strength of our myths without being consumed by the shadow-side.

The first poem, "Exodus in X Minor," sets the scene with the speaker, a "lush siren" who, in a sort of role reversal, is lured to shore by a man who repeats "I love you's" for months in his version of the Greek incantation. The poem fills the page with gorgeous imagery that seems to call out, cry out, this reversal of expectation on the speaker and her setting: "There was a double-headed / deer trophy, a woman who could ignite gasoline / with her tongue…" The double-headed deer looks on as the poem unfolds a frustration in its dramatic irony for the reader. The reader knows the power hidden from the speaker, as if under a spell, from the moment the book opens.

The tension created between what is known and is what is hidden or suppressed—whether by trauma or societal expectations—is carried on throughout this stunning collection by Frazier, just as the poems delicately weave a beautiful balance between the mythical and the relatable. In "The Raven-Haired Seer Visits St. Francis Farm, Run by Catholic Workers in Upstate NY, with the Great-Granddaughter of the Farm's Original Founders," the piece plays with expectation and reality from the title, which sets the reader up for a fairytale, to the end in ways that highlight both the myths we carry with us, the myths that sustain us, and the myths that blur the pain we try to bury:

a toybox with exactly three toys in it: one skeletal artifact

of a GI Joe, one threadbare puppy with a mildewed ear who was losing

his insides, and one—I think it was—doll, which appeared

to be plastic, most of its painted features rubbed off. In some places

it was translucent…

Frazier lets the scene and characters play into the known and unknown, the tension that exists between what can hold us back from truth and maybe why we may need to perpetuate such boundaries. The Raven-Haired Seer sees beyond the boundaries for us, and we are let into the most intimate of secrets, only to be shut out again. "In my dream, she / vanishes and I search, finding only that sad toy box."

The concept of otherworldly ghosts that haunt the speaker in the present, future, and past serves to accentuate further what constrains and fuels us and how what is created to protect us may one day harm us, how the "horn of a saddle in our memory" may fail. The fall inevitably comes. Frazier's poems confront the question of whether the damages and myths created around them serve to protect or harm. Frazier writes in the final lines of "Letter to Diane Arbus": "As a child, I dressed // one October as a crash // test dummy" which leads into the beginning of another Raven-Haired poem set in an October where two girls "shared // a single, childish quest—to witness… // encounter the fearsome dry-iced ephemeral // substance… /… These bodies."

The haunted yet powerful spaces created in Frazier's poems often speak to the emergence of the female body, wrestling with the push and pull of demands, of how to reconcile "secrets / unspooled" with "God's silence" against "cream gingerbread trim" and why the "body harvested darkness" alongside "parents, their grief / still husking the air. Wood chopped and dismembered…" Against the trauma is defiance, however, because the speaker learned to "love rain. The way you love / bourbon. // …I belong to futures now. And will."

The reader, thankfully, is given a glimpse into this resilience before confronting "For Maddy Lerner, Age 6, Accidently Killed at an Outdoor Firing Range in Upstate New York," where the speaker admits

Maddy, I'm scared

to ask how they feel

in the meat of you: the shells

fell warm against

my hand & I saved

the target to hang in my fire

escape window that won't lock.

Though there is an unflinching strength that faces the elegy toward darkness, a territory well-traversed in this collection as a "body transformed / into an opalescent glass globe" and "a razer sharper than anything," it is in the Exodus poems where Frazier lifts the reader out for a moment, directs how to carry on. In each "Exodus in X Minor," the tension eases for a moment, and the speaker is reacquainted with a kind of power and strength, letting up the tension in the dramatic irony between what the reader knows and what the speaker knows. In Exodus are moments where the speaker lifts the glass globe world and body to a new light and "Spirits gathered like locusts salivating I unfurled / my wings and screamed I will not let you take you from us" and "we escaped we are / escaping one carved // tree trunk at a time… / not being but becoming // creatures newer more brightly made"

Frazier's work is interspersed and flanked with stunning artwork by Joanna C. Valente; each piece often asks the viewer to participate, fill in, and imagine what belongs within the blank spaces: a nightgown hangs on what seems to be a spirited "body transformed;" a gravesite sits among the reeds, script unknown, with a bare tree waving its ghost-like arms above; or a bright celebration of a dancing woman, see-through hair and puzzle-like face calling toward the viewer as if to say "name me, name this tune." The dramatic swoop of line fills the page with energy that the work vibrates regardless of whether it is a still life study—brassier, scarf, mirror, lipstick—a landscape, or women embracing. Before the viewer knows it, a whole myth is born in mind—active participation between artist, page, and viewer. Valente's artwork compliments Frazier's collection, which asks the reader to step into a territory that is both familiar and brand new, what is known and buried—to witness a breaking-into, violence, of becoming, despite, and with the help of, the myth.

Visit Fox Henry Frazier's Website

Visit YesPoetry Books' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.