ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Marc Zegans has penned six collections of poems, most recently, The Snow Dead (Cervena Barva Press, 2020), and La Commedia Sotterranea: Swizzle Felt's First Folio from the Typewriter Underground (Pelekinesis, 2019); two spoken word albums; several immersive theatrical productions including, Sirens, Dreams and a Cat (co-written with D. Lowell Wilder, 2020), and many short films. Marc lives by the coast in Northern California. You can find his poetry at marczegans.com, and learn about his creative advisory practice at mycreativedevelopment.com.

January 28, 2022

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

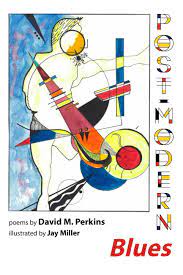

Superpositions: A Review of Post-Modern Blues, poems by David Perkins, illustrated by Jake Miller

Post-Modern Blues

poems by David Perkins,

illustrated by Jake Miller

Ice Cube Press 2021

David Perkins, a poet, veteran of the publishing industry, and Tchaikovsky scholar, brings to Post-Modern Blues (Ice Cube Press 2021), his second collaboration with artist and illustrator Jake Miller, a clutch of competing impulses artfully reconciled, whilst held humanely in tension. Neither trick of the tongue, nor conjurer’s legerdemain, Perkins’ orchestration of this paradoxical simultaneity, operating as a sort of quantum conductor, interleaves this wounded and weary possibilist’s urgent desire to connect, with the wry and sly poke-in-the-eye humor of a poet who’s gone meta on the deconstructionists.

Central to his project is Perkins’ gentle urgency to decisively seize primacy back from the critics, and to reconnect readers with the text, the hand that wrote it, and the tradition it extends. Proceeding from the irony-bereft premise that the post-modern is simply, “… where we are now,” Perkins invites us to embrace all that the tradition has given us — its forms and devices; the modernist’s demand for perpetual novelty through cyclic (if not always dialectic) innovation, and the post-modernist’s fetish for sometimes sweet, sometimes sardonic, parasitic operations on the specimen text. Embedded in this offer to his readers, is a delectably covert arrogation of authority to do just this — to make strong poetry that freely draws on all that came before in spry and novel ways.

Perkins approaches the past not through Bloom’s anxiety bred-of-influence, but as smorgasbord from which influences are delightedly selected and embraced. This de-constraining of the text, as a bid to wrest the locus of interest from its post hoc deconstruction, gives Perkins broad sway to play, which he does with scintillating verve. And, also, to manifest in his poems an embodied depth of meaning writ in loss, longing, love, error and regret, and the ardent desire of the wounded for things somehow, yet, to be all right, that cannot be separated from the poet’s lived circumstances, and that, accordingly, cannot be flattened by objectification as narrative.

This is brave stuff. Perkins’s book, with Miller’s visual sense-making (reminiscent in its forms of Malevich and El Lissitzky, and in its faces, Chagall) functioning more as score than illustration, is a deeply sung, resonantly honest gathering of blues that issue from the place we are now. By warmly pointing his wit and critique at the self-referential, post-modern discourse on poetry (nested within poetry as it is being done), Perkins shows that he can play the game, and in that clears the space to do something different, to strip himself bare and risk saying something that matters.

In this I am reminded of a moment in the short documentary film, Gambler’s Ballad, during which the magician Penn Jillette, learns and performs with his mentor, Johnny Thompson, Thompson’s signature tale, delivered in rhymed verse with sleight of hand aplenty, of the card sharp’s dilemma. Remarking on the risk inherent in performing such a piece, Penn observes “there’s nothing meta in it,” confessing openly the vulnerability inherent in doing a signature piece that is completely sincere. His decision to assume such a risk on behalf of the aging magician’s magician was described by a peer of Penn’s as “an act of pure love.” And that at its essence is what defines Post-Modern Blues. The poet’s raw determination to cry out in the lonely night and connect is pure and hopeful an act of love as can be.

In this wise and generous collection, Perkins gives us a plaintive self, wistful and mourning for what might have been. He’s tangibly aware of the superpositions of possibilities that he and his lovers erased as they made their choices, defining by these actions the once that was and the now that is, knowing fully the might-have-beens that are not. His poems express the alienation and loneliness of one whose life has been exposed wittingly to the post-modern condition. From this chilled and tattered place, Perkins ventures toward connection, braving unvarnished the feeling and public expression of loss by one who has been forced by experience to deny fate.

Perkins’ world, quantum, not deterministic, inhabits a recursive possibility space in which he cannot escape the raw truth that no one forced his (or his lovers’) choices, or that other possibilities were latent until these were made. He shows us by searing example that when we trim the branches of the tree of possible lives, and when we can no longer displace our regret onto an angry god, onto tradition, onto dialectic cycles, we can only stand, observe, mourn, confess, and seek in our current actions some form of redemption:

… Shiny things it seems distract me, and

led me on, and so far gone now (and much too

late), there is no getting back to that alighting

where I first stepped off fatally wrong—so it is.

—from “So Far Gone Now”

To reclaim such pain as real, rather than to dissipate our humanity into “discourse,” restores to our conversation the tragic beauty of standing alone and with regret, but not apology, and renders possible the hopeful endeavor of seeking to make meaning in the lives we are yet living. Such poetry primes us to make life from loss. When it issues from a warm and generous spirit whose playfulness amidst it all shines bright, we know that we have been met with a rare gift. This we have in David Perkins’ Post-Modern Blues.

Visit Ice Cube Press's Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.